795 million people chronically undernourished, with armed conflict a root cause of hunger

Among the billions of people on the planet, one in nine are chronically undernourished, according to the 2015 Global Hunger Index (GHI) released this week by the International Food Policy Research Institute, Welthungerhilfe, and Concern Worldwide. The 10th annual edition of the report also finds that one in four children are affected by malnutrition-related stunting (low height for age) and nine percent of children are affected by wasting (low weight for height).

The GHI presents a multidimensional measure of national, regional, and global hunger. New this year, GHI scores have been calculated using a revised and improved formula , with child stunting and child wasting replacing “child underweight” as two equally-weighted indicators. The remaining indicators are undernourishment (the share of the population with insufficient caloric intake) and child mortality (the percentage of children who die before the age of five). The revised formula also standardizes each of the component indicators to balance their contribution to the overall index and to changes in the GHI scores over time.

The data for these indicators are continually revised by the United Nations agencies that compile them, and the present edition incorporates data and projections spanning the period 2010 to 2016. The resulting index provides scores from 9.9 or lower to denote “low” hunger to 35-49.9 to denote “alarming” hunger.

The interactive map below displays and filters GHI data by country from 1990 to the present.

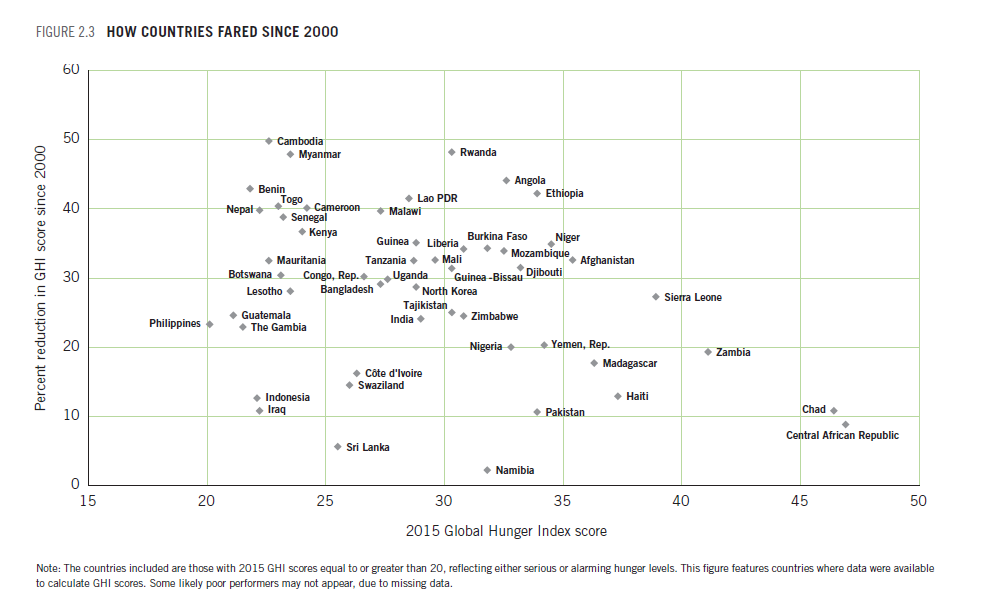

While the overall GHI score for the developing world has decreased by 27 percent since 2000 (all 2000 GHI scores have been updated to reflect the new formula), the latest scores for 52 of 117 countries in the index remain “serious” (44 countries) or “alarming” (8 countries). The worst scores are in Africa south of the Sahara. In terms of specific GHI components:

- Highest proportion of undernourished people: Haiti, Zambia, and the Central African Republic - 48 to 53 percent of the population

- Highest prevalence of stunting: Timor-Leste, Burundi, and Eritrea - more than 50 percent of children under age five

- Highest prevalence of wasting: South Sudan, Djibouti, and Sri Lanka - 21 percent to 23 percent of children under age five

- Highest under-five mortality rates: Angola, Sierra Leone, and Chad - 15 percent to 17 percent of children under age five

It is noted that several of these countries do not have GHI scores for 2015, even though they had alarming or extremely alarming GHI scores in the 2014 report; Burundi, Comoros, and Eritrea did not have the necessary data on undernourishment, and data is missing for Democratic Republic of the Congo. Considered “one of the most food insecure countries in the world” by the World Food Programme, Somalia has never received a GHI score due to “data constraints.”

Indeed, it can be impossible to know exactly how severe hunger is in some of the world’s poorest unstable countries. For instance, this year's report contains GHI scores for Afghanistan for the first time ever, as Afghanistan's hunger levels could not be calculated previously due to missing data. Afghanistan's 2015 GHI score is 35.4, which indicates an alarming level of hunger, but historical data now available as well shows that the country's 2000 GHI score would have been 52.5, surpassing the GHI threshold of 50.

The strong association between armed conflict and severe hunger is a primary theme in the latest report. An average of 42,500 people per day fled their homes last year, and approximately 59.5 million people are displaced by conflict worldwide-- more than ever before. However, more than 80 percent of those affected by armed conflict stay within their countries, says Welthungerhilfe president Bärbel Dieckmann.

“They are the ones who suffer most from severe food insecurity,” he says.

The countries with the highest GHI scores tend to be those engaged in or recently emerged from war. This year’s worst-scoring countries, Central African Republic and Chad, are no exception, while hunger levels have fallen substantially in countries like Rwanda and Angola since the large-scale civil wars of the 1990s and 2000s ended. In his essay for the 2015 GHI, World Peace Foundation Executive Director Alex de Waal recommends a two-prong strategy of establishing stronger mechanisms to prevent and resolve conflicts and an international emergency food relief system to rise to the challenge of the turbulent status quo.

“Food security is not only an essential component of human well-being, but also a foundation for political stability,” writes de Waal. Conflict is not the only significant factor behind hunger and malnutrition in the world, but it is a critical root cause to address.

The report also presents significant positive developments. Of the 117 countries with GHI scores, none hit the hunger index threshold of 50, and 68 countries had scores that dropped from between 25 percent and 49.9 percent since 2000. Seventeen countries reduced their hunger scores by 50 percent or more. Peru cut its 2000 GHI score by 56 percent, while Brazil cut its 2000 GHI score by roughly two-thirds. In terms of regions, East and Southeast Asia saw the largest reduction in their GHI score at 36 percent. With three-quarters of the South Asian population living in India, progress in that country’s indicators carries major weight for the regional score.

Geographic and contextual differences aside, Brazil, Peru, and India all experienced concentrated efforts by government and civil society to address issues of poverty, health, and food security which provide useful lessons learned for other countries. It is clear that while gains have been made, there are many unmet needs to address hunger on a global scale. The inability to calculate scores for a number of countries highlights the importance of data for development and prioritization.

BY: Rachel Kohn, IFPRI

Files: