One year of war in Gaza: Food emergency continues with no end in sight

With conflict in the Middle East now escalating into Lebanon and beyond, Palestinians in the Gaza Strip continue to face dire food security conditions. One year has passed since the October 7, 2023 Hamas attacks on Israeli civilians, triggering the Israeli military retaliation and war that have killed more than 41,000 Palestinians and devastated the livelihoods of Gaza’s population of over 2 million.

Food insecurity in Gaza has slightly attenuated since our previous assessment of last June, when the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) early warning mechanism estimated that nearly all of Gaza’s population faced emergency levels of acute food insecurity. IPC’s Famine Review Committee did not declare famine in June, as food assistance flows into Gaza had then increased from previous low, irregular levels. Humanitarian food assistance has declined since, but an increased flow of commercial food supplies appears to have helped in reducing inflationary pressures and, for now, preventing the occurrence of widespread famine in Gaza.

Humanitarian food assistance under continued stress

While no new IPC assessment has been released since June, some new evidence points towards a renewed, further deterioration of living conditions and dangerously low food supplies.

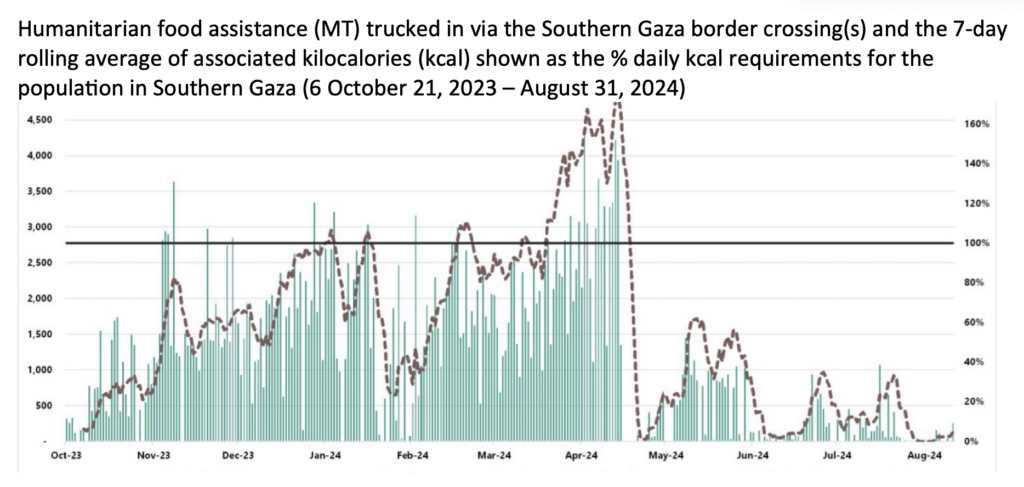

The lion’s share of Gaza’s population—1.8 million people—resides in the territory’s south, and over the past year most of them having been forced to relocate multiple times. They are heavily reliant on food assistance, which has been erratic. A recent assessment of food supplies by FEWS NET estimates that, in August, 2,750-3,050 metric tons (MT) of humanitarian food assistance entered via truck through the only remaining southern border crossing, Kerem Abu Salem/Kerem Shalom—representing a decline of more than 40% from July and of more than 90% since April, the peak of post-October 7 food assistance delivery by truck in southern Gaza. Humanitarian food supplies to the north also declined in July and August.

Following these sharp declines, FEWS NET estimates caloric availability of humanitarian food assistance for the entire Gazan population of 2.2 million people dropped to approximately 15%-20% of the minimum daily requirement in August, down from approximately 30%-35% in July and well below the levels observed prior to the closure of the Rafah border crossing in April (Figure 1). In contrast, food assistance deliveries to the population remaining in the north (about 350,000 people) improved between April and August, rising to cover 70%-75% of minimum caloric needs—up from the well below 50% figure for the first months of the year, though down from peak levels in May, when aid supplies peaked temporarily above minimum food needs.

Figure 1

Increased commercial imports of food

While inflows of food assistance have dropped dramatically, commercial supplies crossing borders have increased. According to FEWS NET’s food supply analysis, an estimated 50,000 MT of food was reportedly inspected and approved for entry in August at the Kerem Abu Salem/Kerem Shalom border crossing by Israel’s Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT).

While FEWS NET was not able to assess this food’s caloric value, people in Gaza do report they now increasingly rely on these supplies. Indeed, respondents to a FEWS NET market survey reported they purchased an increasing share of their food in markets, rather than through food assistance. In southern Gaza, nearly 67% of respondents to a non-representative survey indicated they purchased at least half of the food consumed in their household, a slight increase from July. In northern Gaza, nearly half of responding households said they had bought most of the food they consumed in the market, up from 39% in July.

WFP’s September Market Monitor also indicates increased food purchases in markets, but contrastingly reports that the majority of households throughout Gaza continue to rely on humanitarian food aid as their primary food source. WFP’s survey data indicate that, in August, 63% of households in the southern governorates of Deir al-Balah and Khan Younis reported food aid as their primary source of supply, while 22% obtained most food through market purchases. WFP data further indicate that, in the north, 84% reported food aid and only 7% reported purchased food as their primary food sources.

These apparent contradictions in the data may be the result of a lack of representativity of the samples of both these surveys. Given the fact that food inflation moderated significantly in recent months (see below), it is likely though that larger amounts of commercial flows of food are reaching consumers in Gaza.

The improvements are slight at best, however, and conditions for accessing food are as precarious and volatile, meaning the risk of further and rapidly worsening hunger and malnutrition remains very high, as explained below.

Unstable supplies

First, truck convoys with both humanitarian and commercial food supplies tend to suffer from substantial delays and congestion at border crossings, leading to high rates of spoilage, especially of fresh foods.

Second, transportation to markets and distribution centers is severely limited due to heavily damaged or otherwise impassable roads, ongoing military operations, and inconsistent fuel supplies. In the case of humanitarian convoys passing the Kerem Shalom crossing, for instance, COGAT inspected and approved food trucks for entry each day from August 7-28, but the UN agency for Palestinian refugees UNRWA only recorded receiving humanitarian trucks carrying food on three separate days during that period. In late August, a World Food Programme (WFP) convoy returning from the Kerem Shalom border crossing came under fire at an Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) checkpoint, resulting in a temporary suspension of all WFP operations and movement in Gaza.

Third, convoys have been subject to looting by organized groups, targeting trucks carrying food with smuggled cigarettes. This has also impacted humanitarian food assistance, although its full extent is not known.

Fourth, food market operations are highly dysfunctional and volatile because of the destruction of physical infrastructure, massive displacement of people, and disrupted payment systems. Limited internet availability in Rafah, Deir Al-Balah, North Gaza, and Gaza City due to fuel shortages is impeding traders from conducting their business and preventing consumers making digital payments or accessing cash.

Fifth, and most importantly, the destruction of the livelihoods of most people in Gaza has severely constrained access to food. A June assessment by the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that real GDP plunged by 83% since the start of the war and the unemployment rate has increased to 80% of the working population (up from about 30% before the war). The loss of income sources has been compounded by high consumer inflation. Food prices have increased 2.5-fold since the start of the war, and the overall consumer price index (CPI) increased almost 3-fold (Figure 2). The figure also shows, however, that the pace of inflation has decelerated since April-May with the larger inflow of food and other necessities crossing the border.

Figure 2

Sixth, the destruction of croplands and infrastructure for agricultural production has also limited access to food and income other than from humanitarian assistance. A recent satellite imagery analysis conducted by UNOSAT (the United Nations Satellite Centre) in collaboration with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has revealed a stark picture of the conflict's destructive toll on Gaza's croplands.

Before the war about 160 sq. km (about 41% of the total area of the Gaza Strip) was in use for agricultural production. Since then, approximately 68% of permanent crop fields showed significant declines in health and density (Figure 3). This represents a major further deterioration since the beginning of 2023, when the conflict had damaged about one third of agricultural lands, as reported in a previous blog post.

Figure 3

Source: United Nations Satellite Centre (UNOSAT).Instructions: Click on "swipe" at upper right and swipe vertical line across the map to show difference between October 2023 and latest available data, or with swipe option off, click on inset map at lower left to toggle between the two dates.

The destruction of agricultural land is caused by razing, heavy vehicle activity, bombing, shelling, and other conflict-related dynamics. The estimated damage includes destruction of orchards and other trees, field crops, and vegetables grown in green houses. Nearly all of Gaza’s capacity to produce vegetables and fruits is now gone. Also, the production of wheat has come to a virtual halt. Wheat is the main field crop in Gaza, mostly grown in areas heavily affected by conflict and mass displacement of people in North Gaza and Khan Yunis. Also, livestock holdings have been devastated, including 90% of poultry farms.

The broad loss of agricultural capacity has severely constrained food supplies in the Gaza Strip. Before the conflict, about 44% of household food consumption came from domestic producers, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). The decline in domestic production further pushed up food prices, which increased the most for the affected crops and food items, including wheat flour, eggs, meat, fresh fruit, and vegetables (Table 1). During July-August prices for some of these items stabilized (such as for wheat flour) or even decreased (e.g., sugar and chicken meat) thanks to increased commercial food supplies, but prices further increased for most fruits and vegetables.

Table 1

Food insecurity remains severe despite recent improvements

Thus, at present nearly all food supplies consist of humanitarian assistance and commercial imports, both of which face multiple constraints in crossing borders and then reaching markets and people in need. Amidst the ongoing war with no end in sight, these conditions imply high volatility in food access and continued high risk of famine.

Still, conditions have not reached that catastrophic level. Neither FEWS NET nor IPC’s Famine Review Committee have yet declared famine in Gaza, as critical thresholds have not been passed. In fact, thanks to the indicated increased inflow of food and other necessities, household food deficits seem to have declined somewhat between June and August.This FEWS NET conclusion is based on data from a non-representative survey showing fewer households with emergency or catastrophic food consumption deficits (Phases 4 and 5 in Figure 4). In the north, this share would have declined from 33% in June to 15% in August 2024, while in the south the share dropped from 23% to 13% by these survey estimates. The share of Gaza’s population facing crisis level-or-worse acute food insecurity stood at 60% in the north and 54% in the south in August.

Figure 4

These recent estimates should be viewed with some caution, as they lack more representative assessments and food supply conditions remain volatile. They also should be reason for optimism, as thus far famine has been averted. Nevertheless, the Gaza food crisis continues. Both FEWS NET and IPC continue to classify a high state of food emergency in Gaza. Both the availability of and physical and monetary access to food remain highly volatile on a day-to-day basis, with potential multi-day disruptions occurring at any time due to raids, clearing operations, evacuation orders, and other conflict-related factors. Barring some change in the dynamic of the war, this inconsistency in the population’s day-to-day access to food assistance—coupled with intermittent physical and financial access to commercial food supplies in informal markets—means the vast majority of people in Gaza are likely to face food emergencies (IPC Phase 4) with pockets facing extreme hunger in (IPC Phase 5) in the months ahead.

Rob Vos is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI's Markets, Trade, and Institutions Unit. Opinions are the author's.