By Antoine Bouet and David Laborde

It can be argued that rich countries are becoming more and more open to international trade. In the US, the average tariff on dutiable imports declined from 59.1% in 1932 to 4.6% in 2005, according to the US International Trade Commission. And emerging economies like Brazil, China, and India have recently begun following the same path, supporting the idea that global trade is becoming progressively more free-flowing.

But these decreasing national averages can in fact mask increases in tariffs at the product level. Countries may increase their import duties at the product level from one year to the next in response to changing economic situations, challenges faced by various domestic sectors, or variation in world prices. This is particularly true for rich countries’ agricultural sectors, and for middle-income countries in general.

World Trade Organization (WTO) membership acts somewhat as a deterrent against increased protectionism; the propensity to augment tariffs is lower among WTO members than among non-WTO countries. Before the WTO (or the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) existed, the cyclical nature of protectionism was a much more pronounced phenomenon. Looking again at the US, the average tariff on dutiable imports was 50% in 1894, 40% in 1896, and 52.1 in 1899. The next cycle was even more severe, with the average decreasing uninterruptedly from 49.8% in 1902 to 16.4% in 1920 before being raised again to 59.1% in 1932. The same kind of trend can be seen in throughout Europe during the same period. But what causes these cycles?

Part of the answer can be found in business cycles. During periods of sustained economic growth, unemployment is not a national concern and governments are prone to open their borders to foreign competition, in particular when their trading partners are doing the same. During periods of economic recession, on the other hand, domestic job markets provide fewer opportunities, and any perceived threat to existing jobs is poorly received by countries’ populations. In such times of economic trouble, lobbying for protectionist policies increases more in sectors without comparative advantages, especially when those sectors are small and geographically or socially homogenous.

Just look at events stemming from the October 1929 financial crisis. In early 1930, global unemployment was rising, fear of deflation prevailed, and a lack of public resources (which was more pronounced in countries paying war reparations) prevented governments from remedying the economic meltdown. In this type of economic context, protectionist policies are tempting for policymakers: they (shortsightedly) increase domestic prices and support domestic activity, while providing new public income. However, as seen in the US in 1930, governments often do not correctly anticipate other countries’ retaliation and counter-retaliation for such policies.

A parallel can easily be drawn between the global economic situation of 1930 and the recent economic and financial crises, which have ostensibly fostered renewed demand for protectionism and could lead to trade barriers mirroring those seen during the 1930s. And today’s governments seem to be no better at foreseeing retaliatory measures: in the midst of the 2007 food crisis, several governments entered a cycle of retaliation and counter-retaliation through the use of export bans and export restrictions.

There is one big difference between 1930 and the current situation, though – the WTO. WTO member countries must agree to not raise tariffs above bound duties. For this reason, an increase in tariff protectionism like the one observed in the 1930s is more implausible today. Pascal Lamy stated in his speech at the Lowy Institute in Sydney on March 2nd, 2009 that: “The Doha Round is the most effective way to further constrain protectionist pressures by reducing the gap between bound commitments and applied policies.” The WTO is an international public good that acts as an insurance scheme against potential trade wars. This insurance scheme would be even more effective if WTO members would agree on a Doha Development Agenda (DDA) that would reduce bound duties even further. But talks on the DDA have been at an impasse since 2011.

What is the cost of a continued Doha failure? A recent assessment conducted through the MIRAGE model of the world economy reveals a potential loss of US $2,262 billion in annual trade volume by 2025, thanks not only to lost international trade as a result of the failure of the DDA but also to the implementation of existing tariff bound duties by WTO members.

In this post, we analyze five scenarios: the Doha compromise, as described by the December 2008 WTO modalities, and four protectionist alternatives.

- DDA. The first scenario represents a successful Doha outcome based on the December 2008 modalities. These modalities cover various aspects of market access, including tariff-cutting formulas, country and product flexibilities (for sensitive and special products), special provisions for tariff escalation, tropical products, and long-standing preferences.

- Up to Bound. This scenario examines the potential for WTO countries to increase their tariffs up to their Uruguay Round (UR) bound level over a five-year period (2009-2014). It ensures that the entire binding overhang will be eliminated. In this scenario, only MFN applied rates and non-reciprocal, preferential rates are modified. The only non-reciprocal program that is maintained here is the EU “Everything but Arms” initiative due to the way that this program has been implemented and renewed in the EU legislation.

- Bound & DDA. This scenario combines the DDA scenario and the Up to Bound scenario, but the bound duties that are used here are those derived from the December 2008 package. Therefore, the difference between this scenario and the previous one represents the extent to which the DDA could reduce the capacity of WTO members to augment MFN tariffs.

- Up to Max. To adopt a more realistic protectionist scenario than the “Up to Bound” scenario, historical data were used to determine the highest MFN applied protection rate implemented by every country during 1995–2006. In order to take into account bound tariffs implemented during the Uruguay Round (UR), the minimum between the historical maximum level and the existing bound tariffs was selected and applied to all relevant regions of origin, those for which no preference exists or for which we decided to remove a preference. This Up to Max scenario corresponds to a case in which governments apply the most adverse trade policies of the past 10 years, but still respect their UR commitments.

- Max & DDA. In this scenario, the same combination (DDA plus a protectionist option) is adopted, but the DDA scenario is combined with the Up to Max scenario. As new bound duties have been defined in the December 2008 package and as the tariff applied is the minimum between the highest duty applied during the 1995-2006 period and the newly defined bound duty, this scenario differs from the Up to Max scenario. The difference between these scenarios represents the DDA’s potential benefit as a “preventative” scheme against trade wars.

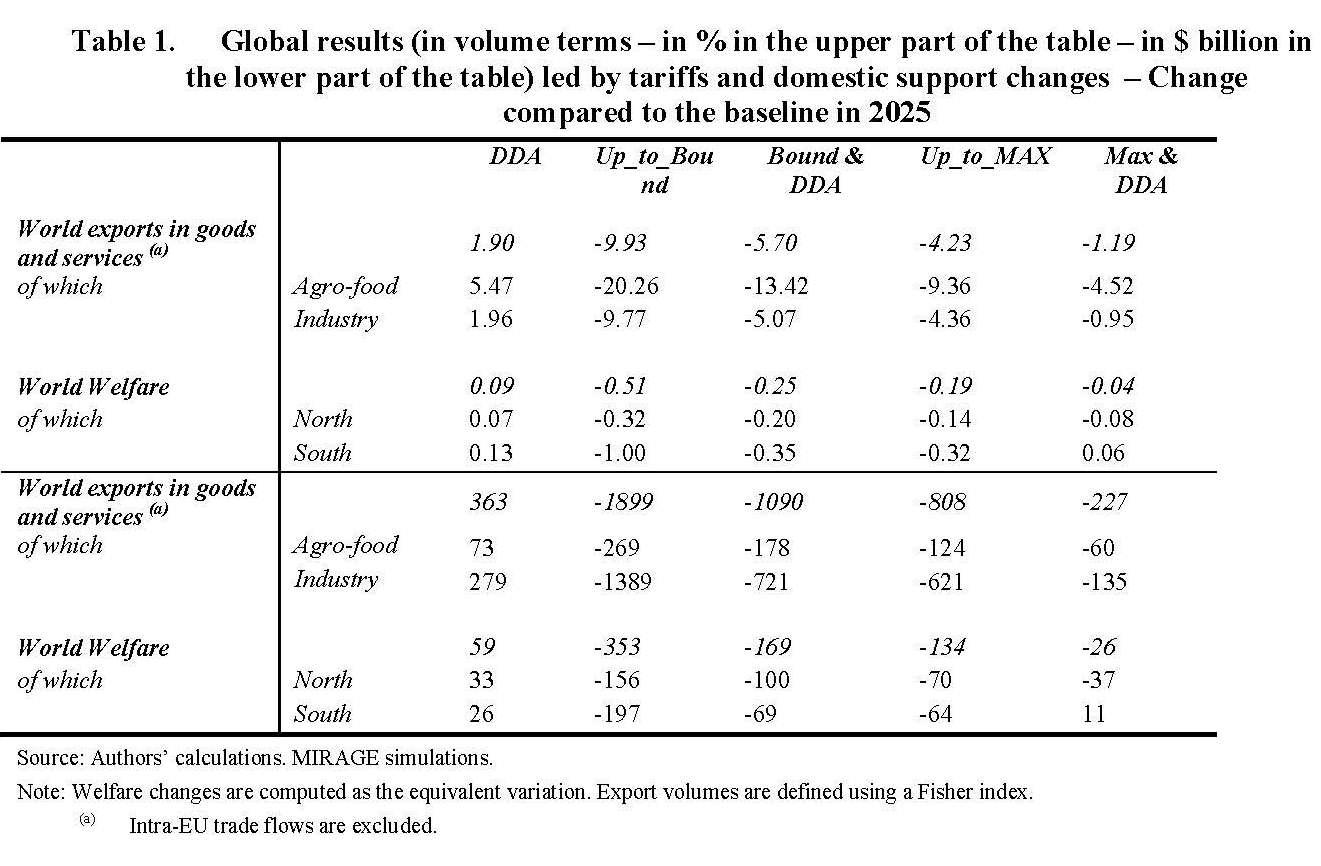

Table 1 shows the results of these five scenarios in terms of global exports and global welfare; these are changes compared to a baseline in 2025, where no policy scenario has been implemented. Under the Doha scenario considered here, global trade is augmented by a mere 1.9 % (US $363 billion) and global real income by US $59 billion by 2025. In case of the Up to Bound scenario, global trade would contract by 9.9 % (US $1,899 billion) and global real income by US $353 billion. In the case of the less damaging Up to Max scenario, global trade would decline by only 4.2 % (US $808 billion).

In the case of an implementation of the December 2008 package and a subsequent augmentation of protection up to bound levels, the decrease in global exports would be only US $1,090 billion; it would be US $1,899 billion if the DDA were not applied. In other words, according to our assessment, DDA implementation can prevent a potential reduction in trade of US $809 billion. If the rise in protectionism reaches the maximum protection applied during the 1996-2006 period, the DDA could prevent a potential reduction in trade of US $581 billion.

During a period of economic stagnation, the failure of the DDA would likely give WTO members the incentive to pursue protectionist policies. In that case, international trade will face a dreadful iceberg: the opportunity cost of not concluding the DDA, US $363 billion in trade, will be vastly outweighed by a potential reduction in global trade of at least US $1,171billion (US $1,899 billion if we consider the “Up to Bound” scenario).

Strikingly, these conclusions are especially true for poor countries. In terms of real income, from a global value of US $193 billion (US $59 billion of global welfare from a Doha Round + US $134 bnbillion of the global welfare losses avoided – scenario “Up-to-Max”), about two-thirds ($ 128 billion) represent the benefits to developing countries. Thus, the cost of a failed Doha Round will fall most heavily on the shoulders of the countries who can least afford it. Since the Doha Agenda has such great potential to benefit developing countries, it is clear that it should, indeed, be considered a Development Round.

References

Messerlin P. 1985. "Les Politiques Commerciales et leurs Effets en Longue Periode." in Le Protectionnisme , ed. B. Lassuderie-Duchene and J.-L. Reiffers. Paris: Economica.

Bairoch, P. 1995. Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Irwin D.A. 1992. "Multilateral and Bilateral Trade Policies in the World Trading System: an Historical Perspective." In New Dimension of Regional Integration , ed. de J. de Melo and A. Panagary. Center for Economic Policy Research.

Evenett S. J. 2013. Protectionism’s quiet Return. . Global Trade Alert, GTA Pre-G8 Summit Report. Center for Economic Policy Research.

Bouet A., and D. Laborde. 2008. The Potential Cost of a Failed Doha Round . IFPRI Brief. Washington DC: IFPRI.

Files: