U.S.-China trade war 2.0: What are the implications for global oilseed markets?

Second in a blog series examining the potential consequences of the recently-proposed U.S. tariffs for global agrifood trade. Read the first post here.

The U.S. government’s most recent tariff measures are strongly focused on China, in what looks to be a replay of the 2018-2019 U.S.-China trade war that resulted in large losses for both countries. That conflict significantly diverted agricultural trade, as China sought other suppliers and the U.S. attempted to find new markets for its products. Each country’s current tariffs targeting the other now far exceed the highest levels of that previous trade war. Depending on their duration, these measures could have serious impacts on the economies of the United States, China, and the global trading system as a whole.

Agricultural trade is at the center of the conflict, as the U.S. is the second-largest supplier of agricultural commodities to China (after Brazil), and China is one of the largest markets for U.S. agricultural exports. This post focuses on the potentially large impacts the new tariffs on global oilseed flows could have on China and the U.S., as well as on other major oilseed exporting and importing countries.

Our modeling exercise suggests that the conflict would wipe out U.S. oilseed exports to China and significantly erode U.S. global oilseed trade. Other countries such as Brazil would likely move to fill Chinese demand but might struggle to do so. China’s oilseed imports and overall global trade in these key products would fall.

Background on the U.S.-China trade conflict

As our April 2 blog post discussed, the U.S. announced a broad set of “reciprocal tariffs” affecting imports from almost all of its trading partners. China was one of the countries hit hardest—a 34% “reciprocal” tariff on top of a 10% duty put in place on February 4 and an additional 10% implemented on March 4, for a combined supplemental rate of 54%. On April 4, China responded by imposing a 34% supplemental tariff on U.S. goods. On April 8, the White House announced that it was amending the April 2 executive order by imposing an additional 50% tariff on China, bringing the combined supplemental duty to 84%.

On April 9, President Donald Trump announced that the U.S. was suspending the imposition of the “reciprocal tariffs” for 90 days and leaving a 10% supplemental duty in place for all countries—except China. For China, he raised supplemental tariffs to 125%. On April 11, China matched the 125% tariffs but indicated that it would disregard any further U.S. tariff hikes.

According to research by Chad Bown of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, average U.S. tariffs on Chinese exports now stand at 124.7% (Figure 1). China’s trade-weighted average tariff on U.S. exports is 147.6%. The trade-weighted average of the new tariffs is over six times the levels prevailing at the time of the previous trade war.

Figure 1

Importance of soybean trade between China and the U.S.

China imported 112 million metric tons (MT) of soybeans during the 2023/2024 marketing year, accounting for 62% of global soybean imports (Figure 2). Since 2000, China’s soybean import demand has grown steeply and steadily at an average rate of 9.2% per year—almost quadruple the growth rate of the rest of the world. China imports soybeans to be crushed into soybean meal, an important protein source for animal feed; and soybean oil used primarily as a cooking oil. China imports other oilseeds, primarily rapeseed (canola) (more than 5 million MT in 2023/2024), other vegetable oils such as palm and sunflower oils, and other oilseed products.

Figure 2

Brazil and the U.S. are by far the largest soybean exporters to China, accounting for a combined export share of 92% in 2024 (Figure 3). Other South American suppliers such as Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay combine for most of the remainder.

Figure 3

Brazil’s recent growth in this area—mostly at the expense of U.S. market share—is particularly striking. In 2000, Brazil’s share of the China soybean market was 20% compared to the U.S. at about 50%, with other suppliers accounting for the other 30%. By 2016, the U.S. share had fallen to 40% and Brazil’s had grown to 45%. The previous U.S.-China trade war cemented Brazil’s current dominance—its share soared to 75% in 2018, while the U.S. share dropped to 19%. Brazil currently accounts for 71% of China’s market, while the U.S. accounts for 21%.

Using the MIRAGRODEP trade model, we simulated the global trade impacts of both countries’ tariffs in place as of April 12. On the U.S. side, these include the supplemental tariffs on China and the 10% supplemental tariffs on the rest of the world. China was assumed to counter-retaliate with a supplemental 125% supplemental tariff on U.S. exports.

That 125% tariff would likely have large impacts on global oilseed trade flows (Figure 4). It would make U.S. soybean imports prohibitively expensive for China—reducing them to near zero. Argentina, Brazil, Canada (rapeseed), and other suppliers would partially offset that impact, but overall China oilseed imports decline by 8.2%, according to the model.

Figure 4

At the same time, as those major non-U.S. suppliers divert oilseeds exports to China, lower-priced U.S. oilseeds would help fill the resulting market void in Europe and elsewhere. Yet for the U.S., this does not make up for lost exports to China; nor does it smooth out the disruptions to global trade, the model suggests. Overall, U.S. oilseed exports decline by almost 39% and global oilseed trade by 4.2%.

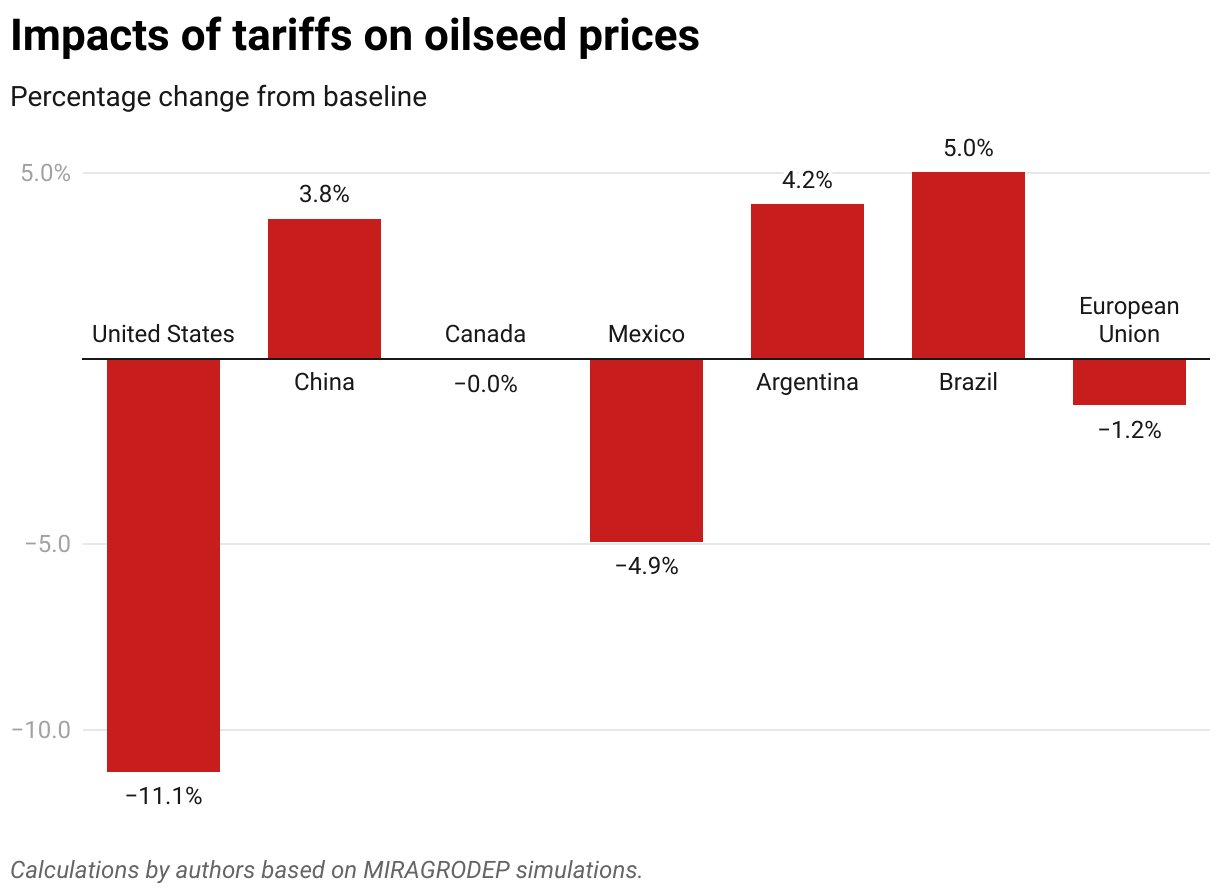

The 125% tariffs result in an estimated 11.1% decline in U.S. oilseed prices (Figure 5). To meet its import demand, China would bid up the price of oilseeds, thus raising them for exporter suppliers such as Brazil and Argentina. China’s domestic oilseed prices are expected to rise by almost 4%. Other oilseed importers, meanwhile, would shift business to now lower-priced U.S. oilseeds. For example, oilseed prices in the European Union are expected to fall by 1.2% and in Mexico by almost 5%.

Figure 5

Short-term impacts

The MIRAGRODEP results are in one sense optimistic in that they assume full adjustments in supply and demand. Yet the likely short-term impacts of another U.S.-China trade war will be driven by a number of complex factors, including how quickly suppliers can react to the new tariff structure.

China oilseed trade is highly seasonal: U.S. and other Northern Hemisphere suppliers export mostly during August-January, while Brazil and other southern suppliers export from February-July (Figure 6). This means that the current tariffs will likely not have a large impact on imports until late summer when the U.S. soybean harvest begins. U.S. export sales data as of April 10 indicate that U.S. soybean exports to China for the 2024/25 marketing year are largely complete (less than 264,000 MT in outstanding sales) and no sales booked for the new marketing year.

Figure 6

A survey of U.S. farmer planting intentions conducted at the beginning of March suggests that U.S. soybean farmers will plant about 38.3 million hectares (ha) this year, down 4% from 2024 levels. The survey was conducted before the extent of the trade war was known. Since then, the soybean-to-corn futures price ratio (an indication of the relative attractiveness of soybeans over corn) has declined, suggesting lower soybean plantings than in the intentions report.

Can Southern Hemisphere producers compensate for the potential collapse of U.S. exports to China? The MIRAGRODEP results suggest that Brazil’s exports to China would need to rise by almost 30%, a large increase by historical standards. During the last trade war, Brazil expanded its soybean plantings by a combined 4 million ha over 2019 and 2020—11% above 2018 levels. Brazil could also draw down stocks as it did during the 2019/2020 marketing year, but current estimated ending stocks for the 2024/2025 marketing year are significantly lower—4.9 million MT compared to 8.1 million MT at the start of the 2019/2020 marketing year.

Another option would be to divert soybeans from domestic crush (making meal and oil) to export. Currently, about 33% of Brazil’s soybean production is crushed domestically. About half of the soybean oil from Brazil’s domestic crush goes towards industrial uses such as biodiesel production. Diverting some of those soybeans towards export markets could help meet China’s import demand, but that would potentially conflict with Brazil’s domestic biodiesel regulations, which mandate a 15% blend rate for diesel fuel.

Other suppliers face similar constraints. According to U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates, Argentina soybean plantings will likely be down this fall, though the trade war could affect those intentions. A recent Statistics Canada survey indicates that Canada rapeseed area is projected to fall 1.7% to 8.76 million ha in 2025, slightly below the five-year average. Canada rapeseed supplies are forecast at 19.4 million MT, 6% lower year over year, due to the decline in output and sharply lower beginning inventories.

Lastly, China could still choose to import soybeans from the U.S. through state trade enterprises including the China National Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs Corporation (COFCO) and the China Grains Reserves Group (SINOGRAIN). A recent Reuters report suggests SINOGRAIN had been purchasing soybean supplies from the U.S. to build stockpiles in anticipation of the potential trade war, implying that SINOGRAIN was willing to absorb the additional duties. Thus while it is unlikely that commercial importers will import from the U.S. given the prohibitive duties, state-owned enterprises could continue to do so if the government is willing to absorb the fees.

Conclusions

The impacts on oilseeds outlined here will likely be felt by other key agrifood commodities if the recent tariff actions result in an extended trade war between the U.S. and China. The U.S. is an important supplier of grains, meats, dairy products, cotton, and other agricultural products (Figure 7).

Figure 7

As with soybeans, U.S. suppliers will likely see lower prices as they divert crops and other agricultural products away from China to other importers. China will pay a higher price as well, as it will have to bid supplies away from other importing countries to meet its domestic needs. Third-country exporters will gain through higher prices, which in the longer term could increase their production, thus eroding overall U.S. market share. Finally, consumers in China and other importing countries will feel these impacts as well, as higher market prices may translate into higher food prices—increasing food insecurity, particularly in poor urban areas.

Joseph Glauber is a Research Fellow Emeritus with IFPRI’s Director General’s Office; Valeria Piñeiro is the Regional Representative for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit; Juan Pablo Gianatiempo is an MTI Research Analyst. Opinions are the authors’.

This work is part of the CGIAR Science Program on Policy Innovations. We thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund.