First in a blog series examining the potential consequences of the newly proposed U.S. tariffs for global agrifood trade.

Citing the persistent U.S. trade deficit and what he considers unfair practices by other countries, President Donald Trump declared April 2 “Liberation Day” and announced a sweeping new set of supplemental tariffs on imports from nearly all major U.S. trading partners. This announcement follows a series of previous actions taken since the beginning of the administration, including 20% tariffs on Chinese imports, 25% tariffs on automobiles and auto parts, and duties on steel and aluminum.

While the broader political and economic implications of these measures have dominated initial headlines, their impact on global agricultural trade could be equally disruptive. Agriculture sits at the intersection of global value chains, international development, and national food security. It is also a sector that has historically been highly sensitive to trade policies, retaliatory tariffs, and sudden shifts in market access. As with the wave of tariffs introduced during the first Trump administration, this new regime could reshape trade flows, drive price volatility, and introduce long-term uncertainty into the global food system.

Overall, according to our modeling analysis, the tariffs could lead to a contraction in global agricultural trade of 3.3%-4.7% and a decline in global GDP of 0.3%-0.4%, with U.S. GDP falling further, by 1%-1.2% (with higher figures reflecting a scenario where countries retaliate against the U.S.).

Beyond such broad global impacts, effects of U.S. tariffs will be both widespread and varied. Depending on how, when, and where they are implemented, the tariffs are likely to lead to both direct and indirect impacts on agricultural sectors, markets, and consumers globally and in many countries.

Direct impacts. New tariffs will raise the cost of imports in the country imposing the tariff and invite retaliatory measures from key trading partners—many of whom are major agricultural importers or exporters. Indirectly, the disruption of trade relationships could lead to the realignment of supply chains, with countries such as Brazil, Argentina, and others stepping in to replace U.S. products in global markets. These changes may provide opportunities for some producers, particularly in the Global South, but they also risk both short-term and long-term losses for U.S. farmers.

Indirect impacts. Globally, these impacts on consumers are also mixed. For exporting countries facing tariffs, prices generally will be lower because more product will be available for domestic consumption. For countries that see an increased demand due to trade diversion, prices will be higher. Higher agricultural prices could have adverse impacts on poorer households, particularly in urban areas where consumers spend a larger share of their income on food.

How are the new ‘reciprocal tariff’ rates set?

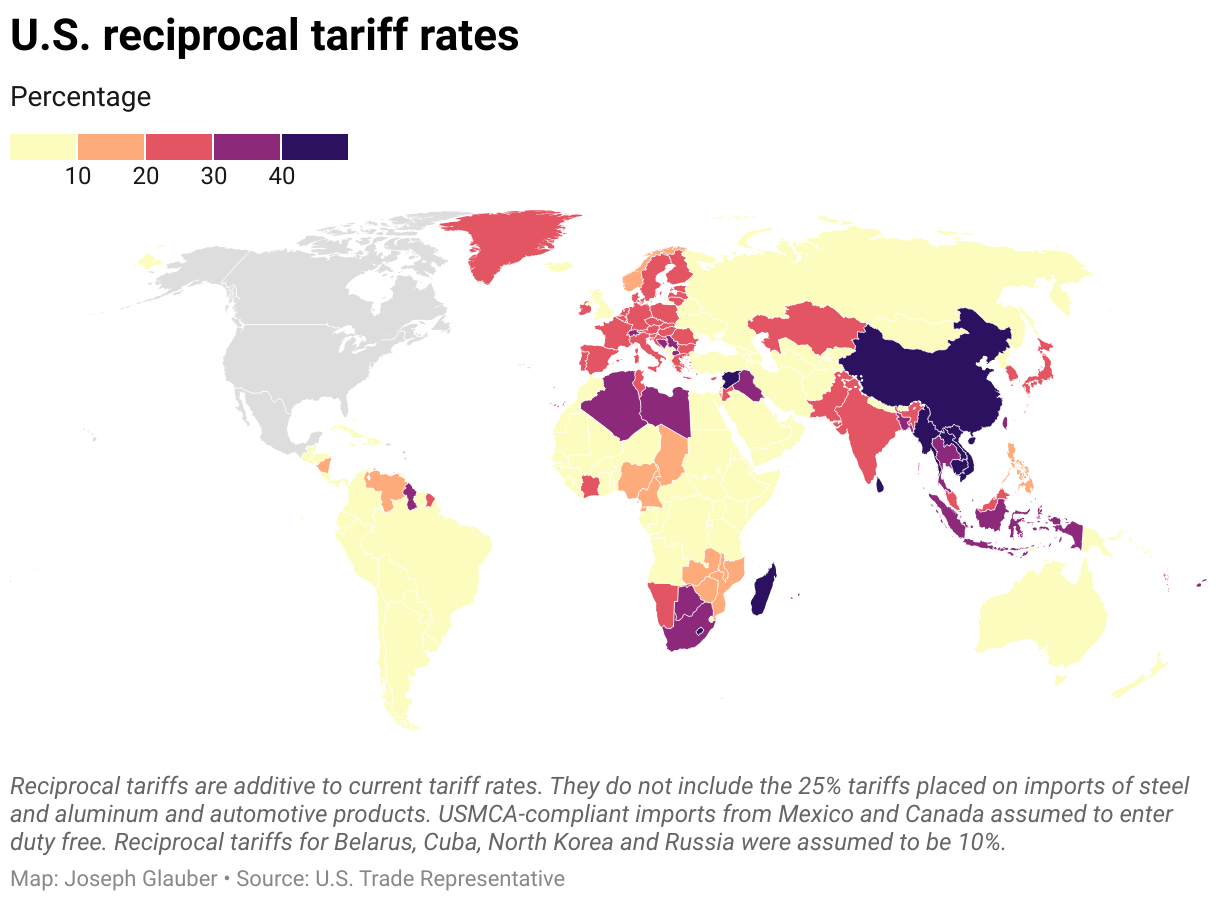

The initial phase of the new tariff regime took effect on April 5, introducing a 10% supplemental tariff on imports from almost all U.S. trading partners. In addition, countries with which the U.S. has the largest bilateral trade deficits will face higher, individualized “reciprocal” tariffs; these are set to be implemented on April 9 (Figure 1). (The new tariffs are termed “reciprocal” by the Trump administration, but they are applied unilaterally rather than in the more conventional sense of an agreed tariff between two parties.) These tariffs are designed to reduce trade imbalances by making foreign goods more expensive and less competitive in the U.S. market.

Figure 1

The new measures are additive to previously existing tariffs, including a 20% tariff on Chinese imports imposed in March. Unlike targeted tariffs that address specific unfair trade practices, this new system broadly applies tariff levels based on the size of each country’s trade surplus with the U.S., without accounting for underlying macroeconomic drivers such as currency valuation.

Certain goods are exempt from the new tariffs, including humanitarian products, items already subject to Section 232 tariffs (such as steel, aluminum, and autos), strategic inputs like pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and copper, as well as energy and mineral imports not available domestically.

Canada and Mexico receive special treatment under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Tariffs remain at 0% for goods that meet USMCA rules of origin, while non-compliant goods face a 25% tariff and non-compliant energy or potash products face a 10% tariff. Overall, the measures represent a major shift toward a more protectionist U.S. trade policy with significant implications for global trade flows, especially in agriculture and manufacturing.

Who will be most vulnerable?

The “Liberation Day” tariffs affect most every country, though the direct economic effect will be felt most by those with higher tariffs and whose trade is more dependent on the U.S. Here we focus specifically on the agrifood sector, given its strategic importance to both global food security and national economies. Agriculture is not only a politically sensitive sector—often at the center of trade disputes—but also highly integrated into global value chains, making it especially vulnerable to tariff shocks.

Figure 2 illustrates the importance of the U.S. as a destination for each country’s agrifood exports, using data from FAOSTAT. Mexico, Central American countries such as Guatemala and Honduras, and parts of South America and the Caribbean are shown in the darkest shades, highlighting their strong dependence on the U.S. market. Canada also appears in dark blue, reflecting the close integration of its agricultural trade with the U.S.

In contrast, countries in Europe, Africa, Oceania, and Asia generally have a much lower share of exports going to the U.S., as it is not a major agrifood trade partner (typically receiving less than 10% of total agrifood exports). Exceptions are countries including Japan and the Philippines where the U.S. accounts for over 15% of their agrifood exports.

Figure 2

Smaller economies, many of which had very small trade with the U.S. in 2024, nonetheless face higher tariffs. For example, countries of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) accounted for only 1.4% of total agricultural goods imported by the U.S., yet their weighted average supplemental tariff rate will be about 20.4% (as compared to the minimum tariff rate of 10% for non-USMCA countries). Among SSA countries with the highest “reciprocal tariff” rates are Lesotho (50%), Madagascar (47%), Mauritius (40%), Guinea (38%), Botswana (37%), and South Africa (30%).

Data show that for most agrifood categories, a significant share of U.S. imports comes from countries facing supplemental tariffs (Figure 3). (Most imports from Canada and Mexico will continue to enter the U.S. duty-free.) Categories including agricultural chemicals (95.1%), spices and herbs (87.0%), coffee and related products (86.4%), and fruit juices (80.9%) are particularly exposed. U.S. imports of inputs including fertilizers, farm machinery, and agricultural chemicals will also be affected by higher tariffs, although some, such as potash from Canada, will continue to be exempt from tariffs.

Given this volume of trade, while the U.S. is targeting its own trade deficits, the ripple effects on agrifood sectors will extend well beyond its borders.

Figure 3

Likely impact of tariffs on the world economy

We analyzed two scenarios of U.S. tariff impacts on global trade. In the first, we imposed the “reciprocal tariff” rates based on the methodology laid out in the memorandum provided by the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. We also include the announced tariffs on steel and aluminum and on autos and automotive parts. The second scenario examines a “tit-for-tat” reaction from countries, which assumes that countries retaliate with tariff measures equivalent to those imposed by the U.S. (Note that the simulations do not include the impacts of retaliations in the services sector.)

We analyze the impacts of the new U.S. tariffs using MIRAGRODEP, a multi-region, multi-sector computable general equilibrium model that aims to explain agricultural trade patterns (as well as those of other sectors) and show how these would change in response to changes in tariff levels. The model is designed to capture medium-term impacts, essentially providing a snapshot of the economy before the shock and another one after the shock has taken effect. As a result, it does not account for short-term effects, meaning that factors such as price volatility, market expectations, and weather events are not incorporated into the analysis.

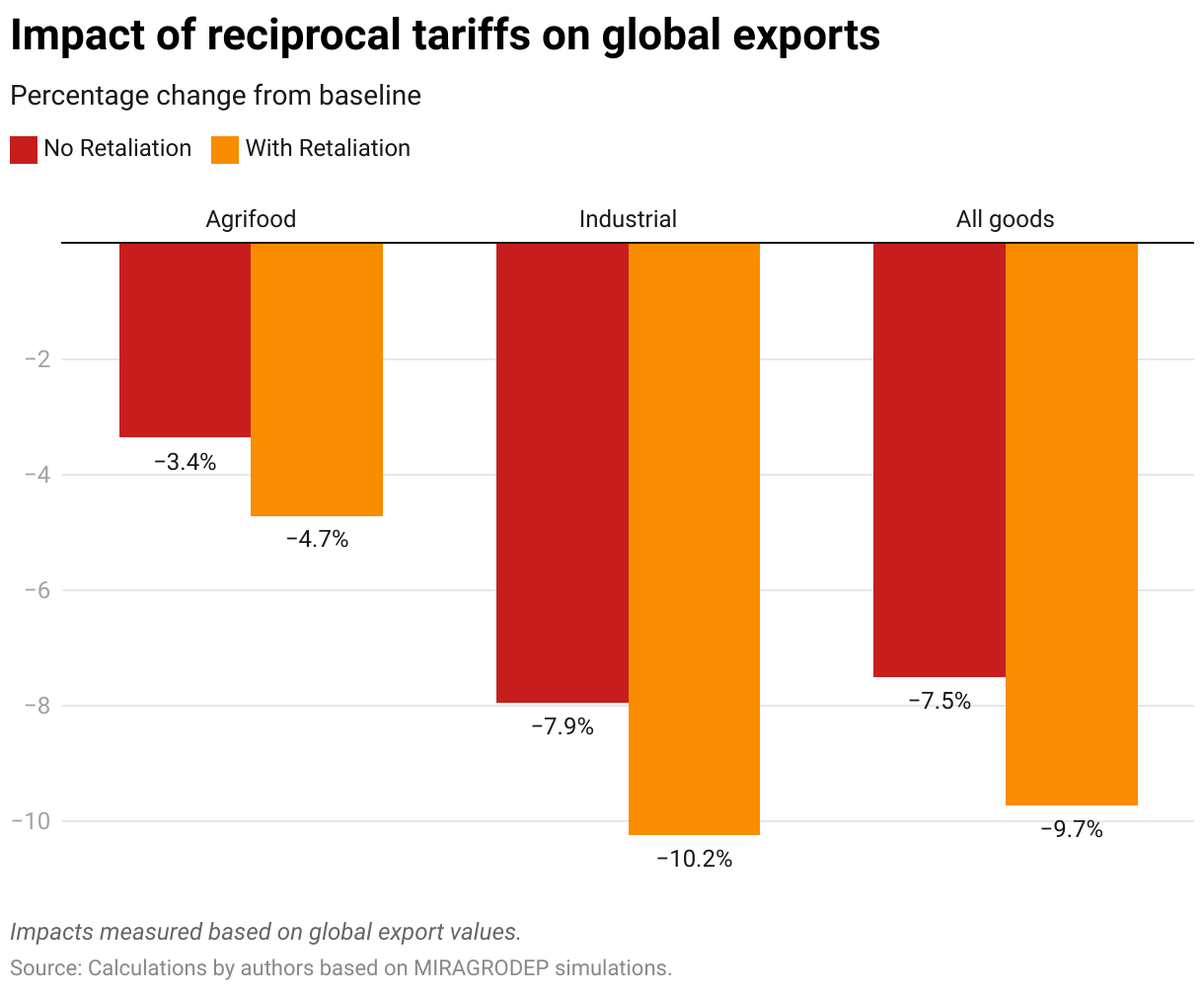

Higher tariffs cause world trade to contract (Figure 4). Total agrifood trade declines by 3.3% from baseline levels under the tariff scenario with no retaliation. As countries retaliate against the U.S., trade falls further—down 4.7%. The impact on trade of industrial goods is even larger, down 7.9% under the no-retaliation scenario, and down 10.2% assuming countries counter-retaliate against the U.S.

Figure 4

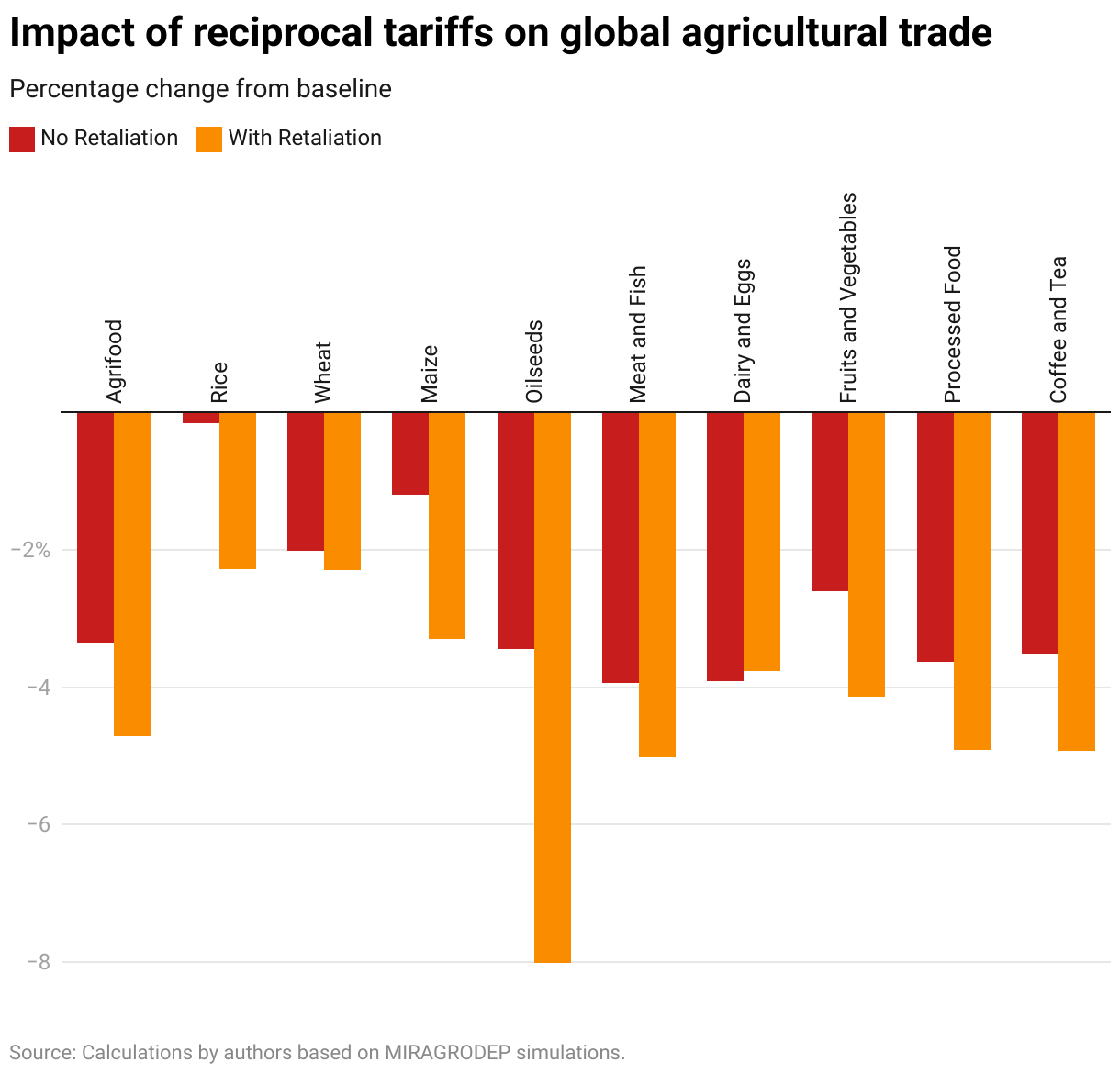

Among agrifood product exports, meats and dairy are hit hardest by the new tariffs, down almost 4% from baseline levels (Figure 5). Processed products and coffee and tea are down about 3.5%. Mostly these losses result from falling U.S. imports due to the increased tariff rates. However, trade losses increase significantly under the retaliation scenario. Oilseeds take the biggest hit as China retaliates with large tariffs of its own on U.S. oilseed imports (54%). China turns to Brazil and other suppliers, but overall trade falls by 8%. Meat and fish products, processed products, and coffee and tea exports decline by over 5%.

Figure 5

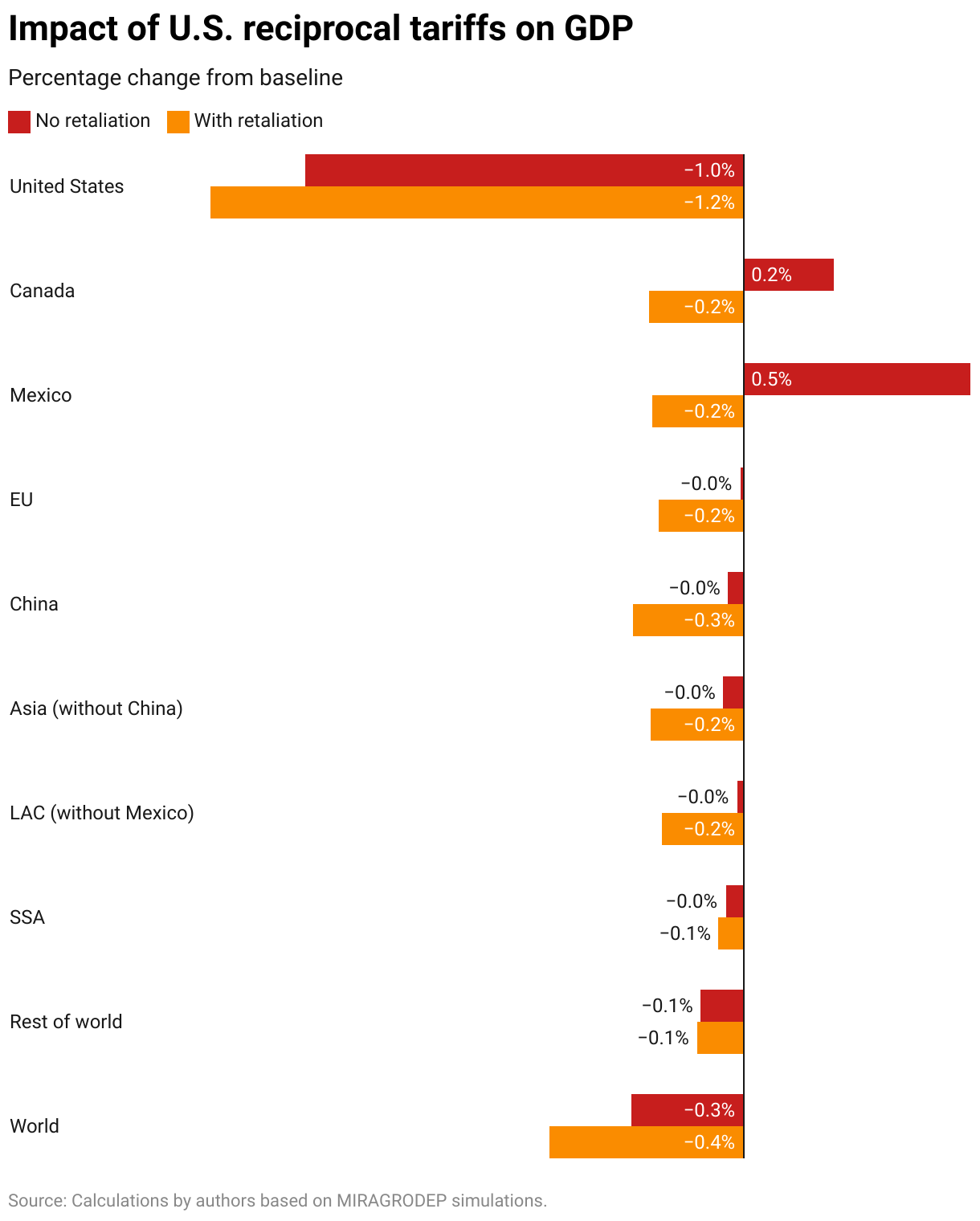

The U.S. tariffs are estimated to cause a –0.3% decline in global GDP assuming no retaliation and a decline of –0.4% in the event countries counter-retaliate against the U.S. (Figure 6).

The largest negative impacts are felt by the U.S., where GDP falls 1.0% assuming no retaliation and –1.2% assuming counter-retaliation. Spared by reciprocal tariffs, Canada and Mexico see a gain in GDP (up 0.2% and 0.5%, respectively) under the no-retaliation scenario. However, even these economies are negatively affected as the trade war spreads in the retaliation scenario (GDP for both countries declines by 0.2%). All other regions are also expected to experience negative economic impacts. While sub-Saharan Africa may show only a modest contraction in overall economic output, the consequences could be more severe when considering its limited fiscal space and the potential implications for debt repayment and financial stability.

Figure 6

Conclusions

The new tariffs put in place by the Trump administration will likely have disruptive effects on the global economy. Based on the modeling results presented here, we expect global agrifood trade to contract by 3.4%—resulting in lower GDP for most countries and regions. Unfortunately, the scenario is even worse (–4.7%) if countries counter-retaliate against the U.S. as trade and GDP fall even further.

As the U.S. faces trade barriers from countries such as China, other countries including Brazil, Argentina, and those of the European Union will step in to fill the gap, particularly in markets for key commodities such as soybeans, beef, and corn. This shift is expected to reshape the global agricultural market, with countries from Latin America and beyond capitalizing on the opportunity to expand their exports, diversifying the sources of these essential commodities. The impacts on sub-Saharan Africa and Asia (excluding China) are likely to be small and mixed. Agrifood trade for these regions contracts as exports to the U.S. fall with the imposition of tariffs, but shows slight gains through trade diversion when countries impose counter-retaliatory tariffs against the U.S.

While the current situation presents significant opportunities for emerging agricultural exporters, it also likely marks a permanent loss of market share for the U.S., especially in key markets such as China. As countries in the Southern Hemisphere forge deeper trade ties with major importing nations, the U.S. could struggle to reclaim its former position, leading to a long-term realignment of agricultural trade flows. Notably, South-South trade will increase as China deepens its trade relationships with Latin American countries, reshaping global agrifood supply chains in the process.

But with trade diversion comes also the threat that countries may choose to raise tariffs more generally. Such was the case in the early 1930s as countries responded to the U.S. Smoot-Hawley tariffs with tariffs of their own. As the economic historian Douglas Irwin and others have pointed out, such measures contributed to the contraction in global trade and exacerbated the economic hardships of the Great Depression.

Joseph Glauber is a Research Fellow Emeritus with IFPRI’s Director General’s Office; Valeria Piñeiro is the Regional Representative for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit; Juan Pablo Gianatiempo is an MTI Research Analyst. Opinions are the authors’.

This work is part of the CGIAR Science Program on Policy Innovations. We thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund.