Impact of proposed U.S. tariffs on agricultural trade flows in the Western Hemisphere

With new U.S. tariffs on Canada and Mexico now in effect, what are the potential impacts on trade among those countries and across the Western Hemisphere?

In a previous post, we examined how the tariffs could potentially impact countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) based on current agricultural trade patterns between the United States and its neighbors in the hemisphere. Here, we extend that analysis, examining how tariffs on imports to the U.S. from Canada and Mexico could affect intra-regional trade between the three countries and across Central and South America and the Caribbean.

Focusing on agrifood trade, this post summarizes recent model-based analysis to be published in more detail in a forthcoming report. It considers two scenarios. The first is based on the U.S. 25% additional tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico (energy resources from Canada have a lower 10% tariff), that took effect March 4. The second scenario considers the impacts if Mexico and Canada retaliate against those measures with across-the-board increases in tariffs on U.S. imports.

Modeling scenarios show that the tariffs would significantly reduce trade in a variety of products between the U.S. and Canada and Mexico, create potential openings for other countries to expand exports, and have a range of other impacts as trade patterns respond to the disruption.

Current trading patterns

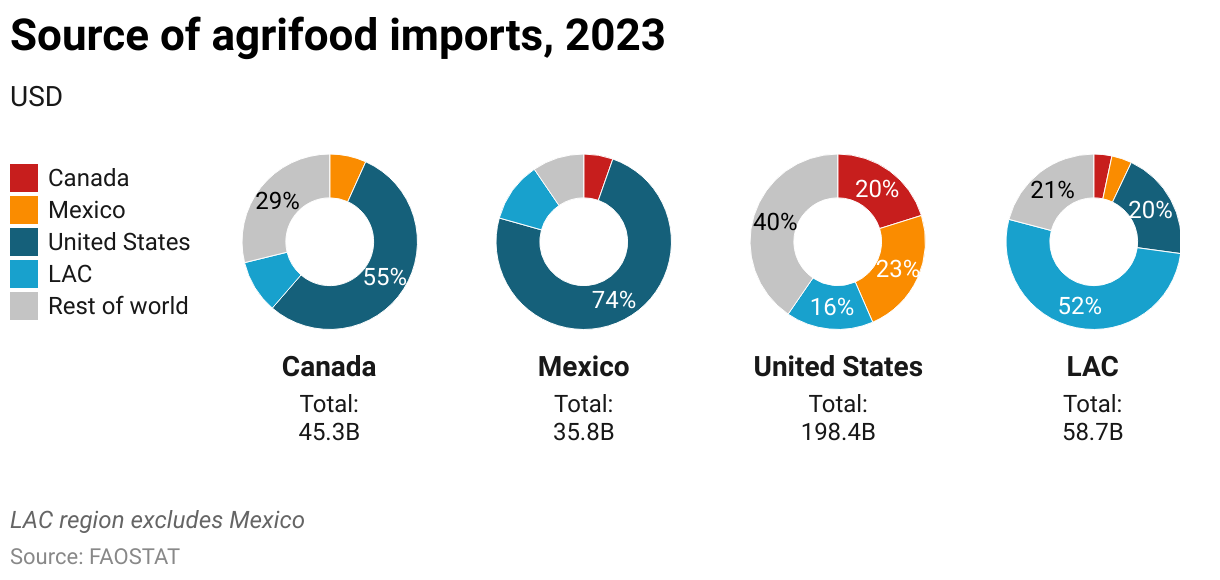

Under a continental free trade regime started in 1994 with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) through the current U.S.-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Agreement (USMCA), signed in 2019, North American agrifood trade has become highly integrated. In 2023, total bilateral trade in the region topped $285 billion—more than triple that of 2005. Almost 90% of Mexico’s agricultural exports and 60% of Canada’s agricultural exports went to the U.S. in 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Agrifood export levels between the U.S., on the one hand, and Mexico and Canada, on the other, are about equal. Yet the latter two countries account for only about one-third of total U.S. agrifood exports. At the same time, bilateral trade between Canada and Mexico is comparatively small: Canada exports to Mexico account for less than 3% of its total agricultural exports, while Mexico exports to Canada account for less than 2% of its total agricultural exports.

Outside North America, as discussed in our previous post, countries in Central America and the Andean region tend to be more dependent on USMCA markets, while the major exporting countries in the Southern Cone region (such as Brazil and Argentina) export proportionately less to the U.S., Mexico, and Canada, which receive only 12% of total LAC exports (excluding Mexico).

Import patterns show the degree to which regional trade has become integrated. USMCA members have similar levels of intra-regional concentration (Figure 2): LAC is also an important supplier of agricultural exports to the region, accounting for 10% of Canada’s agricultural imports, 11% of Mexico imports, and 16% of U.S. imports. On the import side, LAC imports from Canada and Mexico are relatively small, accounting for about 7% of total agrifood imports by the region. U.S. exports to LAC are more than three times that level, accounting for 20% of total agrifood imports.

Figure 2

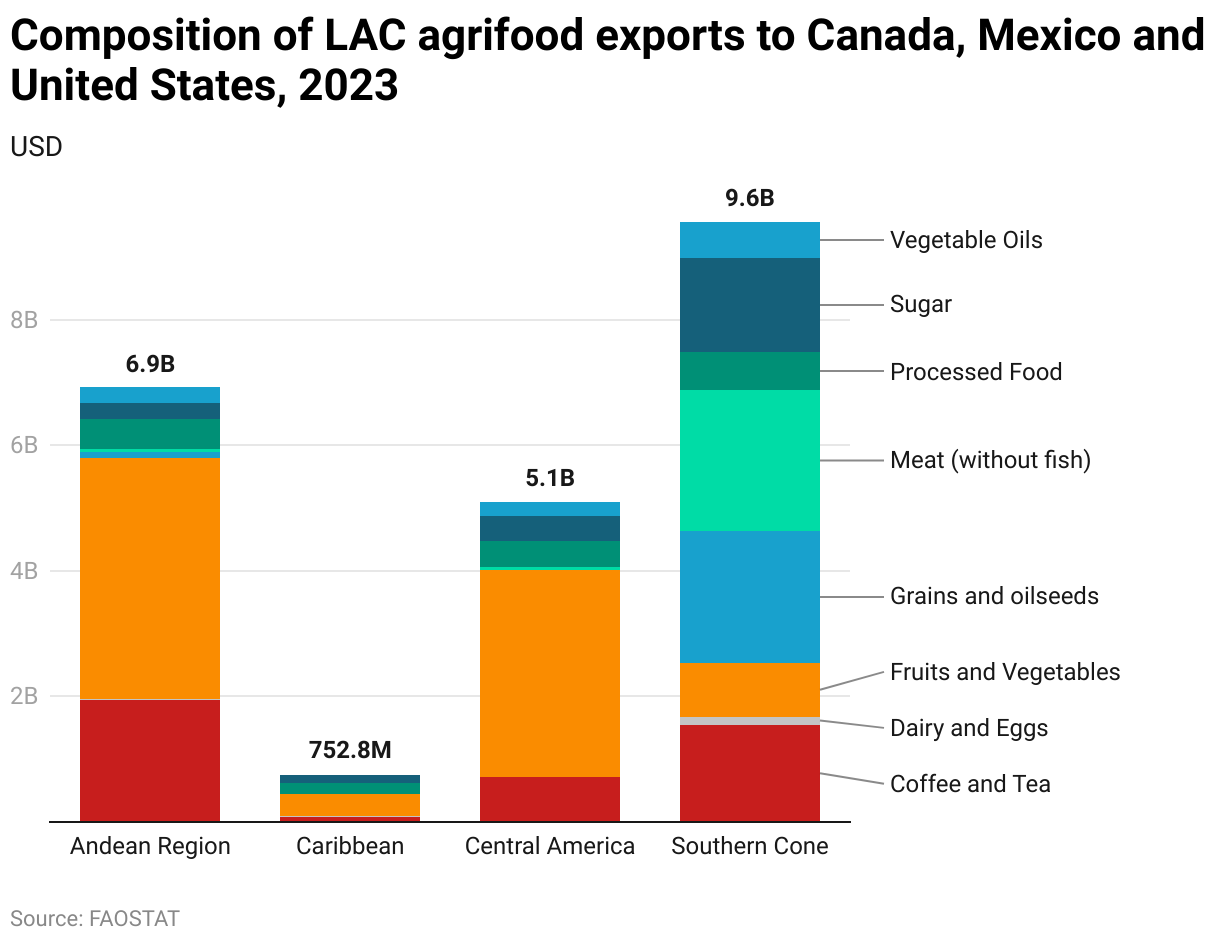

The composition of LAC agrifood exports to Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. differs by subregion (Figure 3). Fruits and vegetables, coffee and tea, sugar, and processed products are important exports for all LAC subregions but the Southern Cone is also a major exporter of grains and oilseeds.

Figure 3

Impacts of tariffs on trade flows

We analyze the impacts of U.S. tariffs using MIRAGRODEP, a multi-region, multi-sector computable general equilibrium model that aims to explain agricultural trade patterns and show how these would change in response to changes in tariff levels. While the model provides simulated output for other economic sectors and regions, we focus the analysis in this post on trade patterns in the Americas as the LAC region is an important supplier of fruits and vegetables, coffee, and other products to the U.S. and is a major exporting region for grains and oilseeds as well.

In the first model scenario, imposing 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada causes agrifood exports to the U.S. to fall by 46.4% and 60.5%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1

Bilateral trade between Mexico and Canada increases by 33%, but it is not enough to offset the losses in the U.S. market. Moreover, due to declining terms of trade and a weakened Canadian dollar and Mexican peso, imports from other regions to those countries decline as well. Overall, in a no-retaliation scenario, total agrifood imports fall by almost 15% for Canada and 20.3% for Mexico.

Tariffs cause a sharp drop in total U.S. agrifood imports (down 10.2% from baseline levels under the no-retaliation scenario). U.S. imports from LAC and the rest of the world increase to offset some of the decrease in imports from Canada and Mexico.

A second scenario with counter-retaliatory tariffs on U.S. imports results in sharp declines in U.S. agrifood exports to Canada (down 66.3%) and Mexico (down 68.6%). To offset those declines, bilateral trade between Mexico and Canada increases, with imports more than doubling for both countries. Imports from LAC and other regions increase as well, but overall, agrifood imports are down by 25% for Canada and almost 35% for Mexico.

For the U.S., the tariffs on Mexico and Canada have the largest impact on imports of fruits and vegetables, processed foods, and meat and fish (Figure 4). This result is not surprising given the importance of these products in the U.S. import profile. Counter-retaliation against imports from the U.S. causes large drops in imports of processed products, and in the case of Mexico, grains and oilseeds.

Figure 4

Implications for LAC agrifood exports

As discussed in the previous section, LAC agrifood exports to the U.S. increase when the U.S. places tariffs on imports from Mexico and Canada. Likewise, when Mexico and Canada counter-retaliate against U.S. imports, those countries turn to LAC (and other regions) to help offset the decline in imports from the U.S.

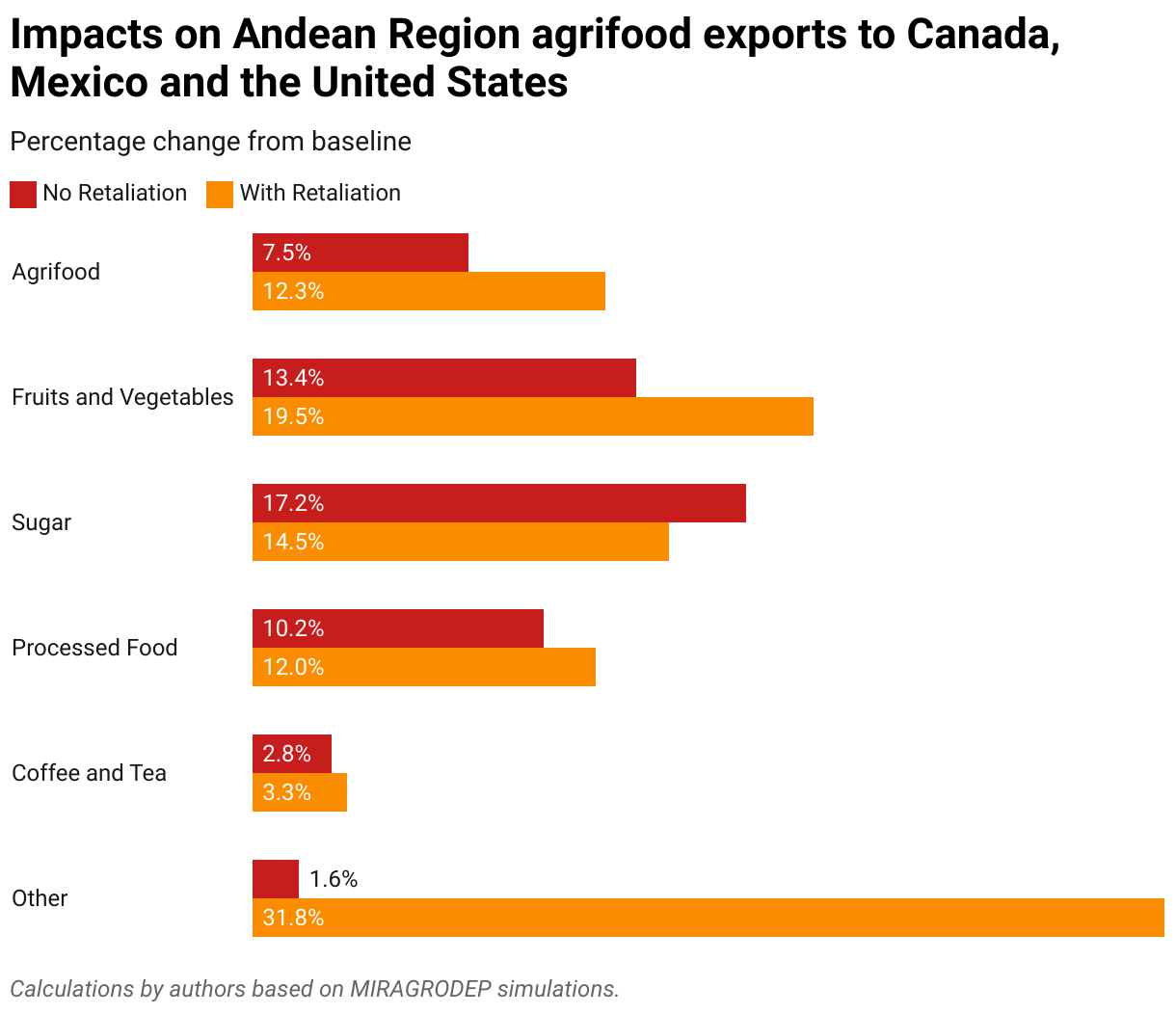

In the Andean region, agrifood exports to Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. increase by 7.5% in the no-retaliation scenario (Figure 5). Most of the gains (95%) come from increases in exports of fruits and vegetables (up 13.4%), processed food products (up 10.2%), and coffee and tea (up 2.8%). Andean region agrifood exports increase by 12.3% under the counter-retaliation scenario.

Figure 5

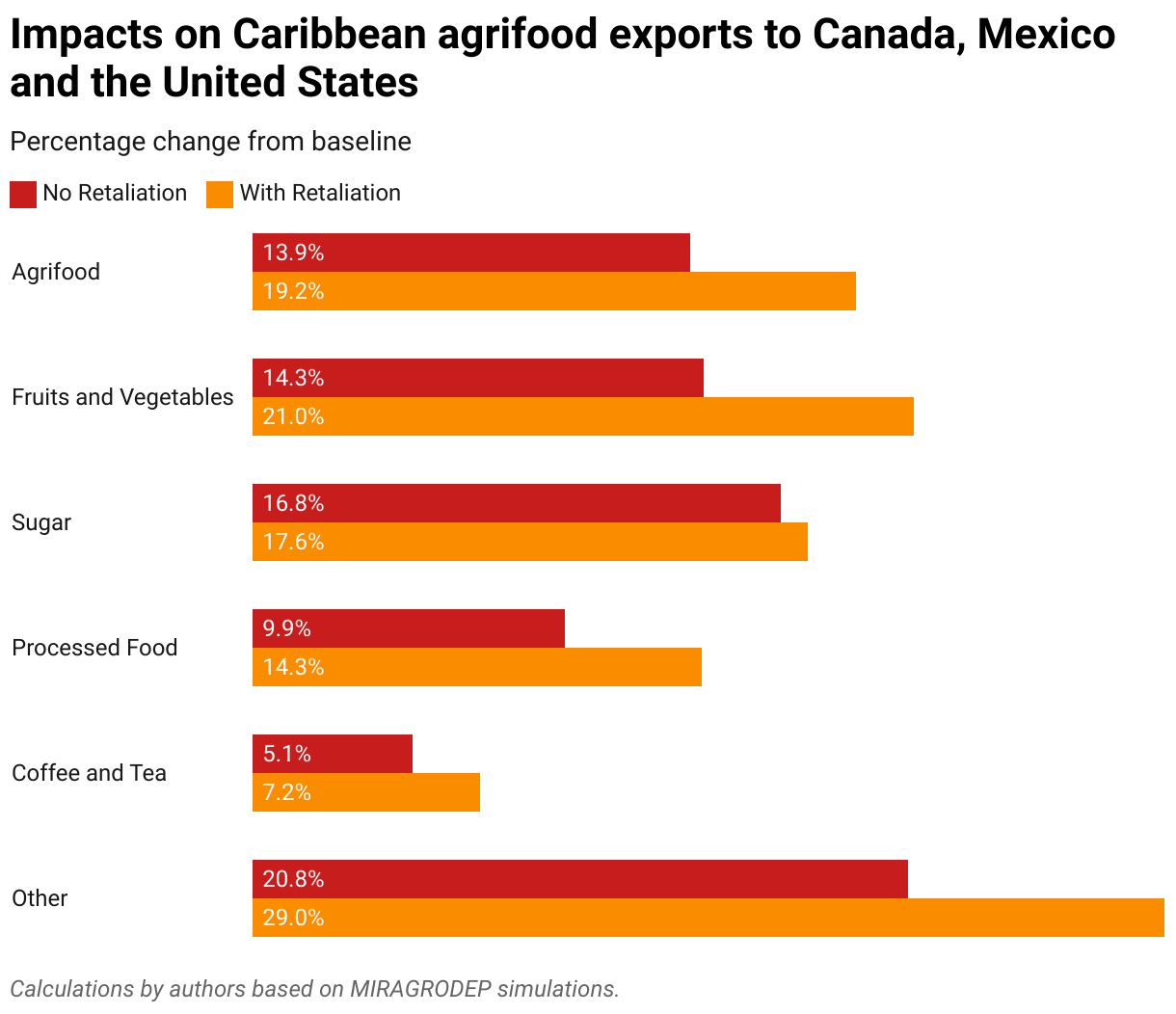

Caribbean agrifood exports to Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. increase by 13.9% (Figure 6). Exports of fruits and vegetables, processed food products, sugar, and coffee and tea account for over 73% of the total export gain. Exports from the Caribbean increase by 12.3% when Canada and Mexico impose counter-retaliatory tariffs.

Figure 6

Central America also gains with the trade disruptions caused by tariffs (Figure 7). The region’s agrifood exports to Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. increase by 7.4% as a result of the U.S. imposing tariffs on its USMCA partners. Exports of fruits and vegetables, processed food products, and coffee and tea account for about 85% of total export gains. Agrifood exports from Central America to Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. increase over 19% under the counter-retaliation scenario.

Figure 7

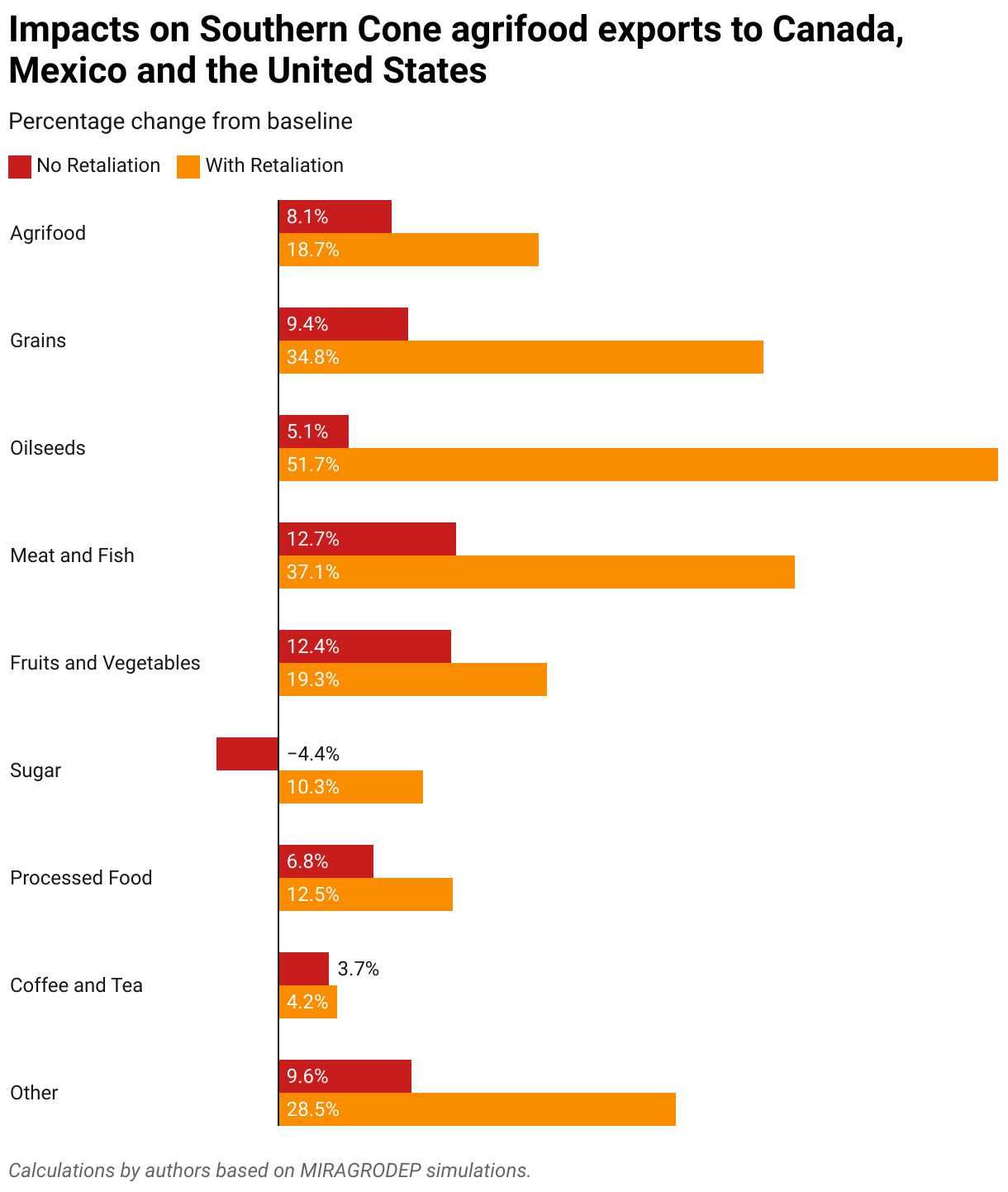

Southern Cone exports increase by 8.1% in the no-retaliation scenario. (Figure 8). As in the other LAC regions, export gains are led by fruits and vegetables (up 12.4%), processed food products (up 6.8%), meats and fish (up 12.7%), and coffee (up 3.7%).

Under the counter-retaliation scenario, Southern Cone agrifood exports increase by almost 19%. Exports of grains increase by almost 35% and oilseeds by 52%; together these account for about 13% of the total increase in Southern Cone agrifood exports to Canada, Mexico, and the U.S.

Figure 8

Impacts on intra-regional LAC trade

Increased LAC agrifood exports to Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. come at some expense of LAC intra-regional trade (Figure 9). Overall, LAC agrifood exports to other countries in the region decline by 1.5%. The impact is larger for those regions more highly integrated into the North American market (Caribbean, Andean Region, and Central America) and less for the Southern Cone region.

Figure 9

Longer-run strategic considerations for LAC

A trade war involving the USMCA region would present opportunities for LAC exporting countries. Our analysis suggests the region would gain, particularly for exporters of processed food products, fruits and vegetables, coffee and tea, and meats and fish. Grain and oilseed producers could gain as well if Mexico and Canada take counter-retaliatory measures against the U.S.

Nonetheless, trade wars bring uncertainty to global markets that are not necessarily captured in these model results. The results are considered static in the sense they reflect the full adjustment of all sectors in the economy to the new tariff structures; in reality, full adjustment can take time as producers react to changes in market prices. In the short run, displaced agrifood trade from North America could present increased competition in other regions (for example, Europe or Asia) which could adversely impact LAC exporters. Increased LAC trade to Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. also could adversely affect intra-regional LAC trade, particularly in the short run.

Joseph Glauber is a Research Fellow Emeritus with IFPRI's Director General's Office; Valeria Piñeiro is IFPRI Regional Representative for Latin America and the Caribbean; Juan Pablo Gianatiempo is a Research Analyst with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit.This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed. Opinions are the authors'.