High global phosphate prices pose potential food security risks

Related blog posts

Fertilizer prices experienced a significant surge in 2021, driven by the post-COVID 19 global economic recovery. Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine propelled prices even higher. Broad economic sanctions on key fertilizer exporters Russia and Belarus exempted agricultural products but triggered further economic disruptions. Overall, the conflict heightened market uncertainties regarding the availability of potash, phosphate, and nitrogen-based fertilizers in international trade.

All fertilizer prices have come down from their peaks in 2022, but price levels today remain generally higher than pre-pandemic levels (Figure 1). For example, urea prices are about 50% higher than they were in January 2020 and phosphate prices about double.

Figure 1

Higher global prices and continuing market uncertainty over phosphates pose potential problems for food security. These key fertilizers provide plants with phosphorus, an essential nutrient for plant growth and development and agricultural productivity. Yet production impacts of persistent high prices unfold slowly. While a decline in nitrogen use can have immediate impacts, a similar shift in phosphate applications takes a longer time to affect productivity. However, if elevated phosphate prices lead to sustained lower use by farmers, global food production could be impacted.

Why have phosphate prices remained high?

Costs of raw materials are elevated

The production of ammoniated phosphate fertilizers, such as the most commonly used diammonium phosphate (DAP) and monoammonium phosphate (MAP), depends on the availability and accessibility of several critical raw materials, namely phosphate rock, sulfuric acid, and ammonia.

While rising costs of these inputs contributed to the increase in phosphate fertilizer prices in 2021 (Figure 2), they alone do not fully account for current price levels. Indeed, the premium associated with the phosphorus component in DAP and MAP remains historically elevated.

Figure 2

Phosphate supply is concentrated

The supply of phosphate fertilizers is geographically concentrated in regions with significant phosphate rock reserves. From 2018-2022, China, Morocco, the United States, and Russia collectively accounted for nearly 80% of the global annual production of ammoniated phosphate fertilizers of approximately 65 million metric tons (MT).

In terms of trade, more than half of the phosphate fertilizers produced globally are exported. China, Morocco, Russia, and Saudi Arabia constitute approximately 80% of global DAP and MAP exports, underscoring the highly concentrated nature of supply to the export market—a factor contributing to higher prices.

China imposes export restrictions

China implemented export restrictions on phosphate fertilizers in spring 2021, prioritizing availability and affordability for its domestic market. China exported an average of 9 million MT of ammoniated phosphates annually in 2019-2020 and reached a record 10 million MT in 2021. But in 2024, exports were only 6.6 million MT (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Other suppliers have not replaced lost exports from China

While Chinese phosphate exports decreased, exports from Russia and Saudi Arabia have remained stable, with production in both countries already operating at maximum capacity. Export volumes are projected to remain unchanged until new production capacity becomes operational, by 2027-2028.

Meanwhile, Morocco has increased phosphate exports since 2022. However, this growth has been gradual and falls short of compensating for lower Chinese exports (Figure 4). Moroccan production has also been increasingly diverted towards other phosphate fertilizers, such as triple superphosphate (TSP), although these markets remain smaller than DAP and MAP markets.

Figure 4

Import barriers exacerbate the situation in the U.S.

Since November 2019, U.S. imports of phosphate fertilizers from Russia and Morocco have been subject to significant tariffs following an investigation initiated at the request of domestic producers.

Since the imposition of import duties, total U.S. import volumes have declined, a shortfall that domestic producers have been unable to fully offset (Figure 5). Simultaneously, import sources have shifted to other, often more expensive, origins. Compounding these challenges, domestic phosphate production has faced disruptions, notably from hurricanes that forced temporary plant shutdowns.

Figure 5

China’s phosphate export restrictions have significantly impacted global supply and played a significant role in higher prices. In this highly concentrated market, the gap has not been completely filled by other exporters—helping to keep prices high. While import duties exacerbate the situation in the U.S., all importing countries have been struggling to meet domestic demand.

Implications for crop producers

A problem of availability

Elevated prices have discouraged phosphate imports; buyers have expected phosphate prices to decline as prices for other fertilizers have done. This cautious approach has led to slower import activity and declining stock levels in key markets.

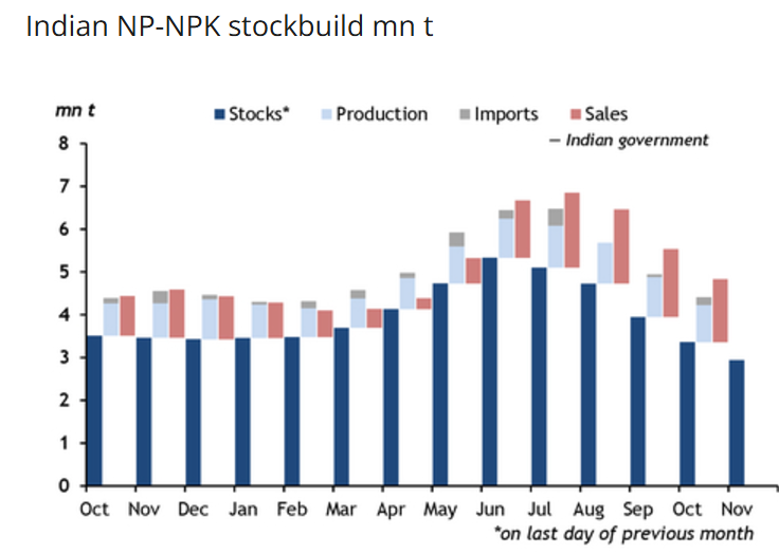

Stock levels reached historical lows at the end of 2024 in major agricultural markets. In fact, the scarcity of DAP during critical sowing periods in India (Figure 6) has sparked public protests, underscoring the urgency of addressing supply constraints and stabilizing markets to prevent disruptions in agricultural activities.

Figure 6

A problem of affordability

High phosphate prices have resulted in a significant deterioration of affordability—phosphate costs relative to crop prices—since 2021. While both surged in 2021-2022, most crop prices have since come down, while phosphate prices remain elevated.

There are growing concerns that the affordability issue may negatively impact phosphate applications. In its November 2024 update, the International Fertilizer Association (IFA) revised its phosphate demand projections downward compared to its May 2024 forecast, now anticipating a slower growth rate of phosphate use for 2024 and 2025 in comparison to 2023 (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Specific country cases

While the global situation presents significant challenges, the realities differ across individual countries. In China, despite its phosphate export restrictions, domestic market prices remain elevated and affordability has not returned to "normal" levels, particularly for critical crops such as rice and maize (Figure 8). Given these conditions, it appears unlikely that Chinese phosphate exports will resume in the short term.

Figure 8

In Brazil, the phosphate fertilizer supply situation is less critical than in other countries. Stock levels are reportedly relatively healthy compared to previous years. However, existing stocks consist of high-priced material, which has deterred farmers from purchasing phosphates amid affordability concerns (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Getting a sense of the impacts of elevated global phosphate prices in sub-Saharan Africa is more challenging due to a lack of data on phosphate markets. However, nitrogen fertilizer price data show that domestic prices for urea have receded at a slower rate and remain higher than global prices in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal. The difference is effectively enormous in local currency units vs. U.S. dollar prices. This price wedge between international and domestic nitrogen fertilizer prices, along with the persistence of global phosphate fertilizer prices above pre-shock levels, suggest that phosphate fertilizer prices in these countries are still substantially elevated.

While phosphate fertilizer consumption contracted less in sub-Saharan Africa than in other regions on average, several countries saw substantial declines. Consumption in Kenya contracted by 42% in 2020-2022 compared to 31% for nitrogen fertilizer consumption (Figure 10). Nigeria experienced a similar large reduction in phosphate consumption compared to nitrogen fertilizers in 2021-2022.

Figure 10

While such evidence indicates that farmers in some countries cut back on phosphate use more than nitrogen use, overall sub-Saharan Africa application rates for both types of fertilizer are far behind other regions. Thus low initial use likely dampened the impacts of the price shock. Even so, evidence of reduced consumption in some countries suggests that sustained elevated prices could still dent or reverse the previous trend of increasing phosphate fertilizer use in the region.

Why high prices matter

Persistently high phosphate prices pose the risk of a slow-rolling erosion of agricultural productivity in many countries. As soils can retain phosphorus for extended periods, reducing or skipping phosphate applications may not have immediate yield impacts. However, if farmers stung by continuing high prices measurably cut back applications over the course of several seasons, lower yields could result—with higher food prices to follow.

Such an outcome is not guaranteed; there are several mitigating factors. Cropping practices can help restore phosphorus content in soils after each planting cycle. With the decline in nitrogen and potash prices, farmers may allocate more of their budgets towards purchasing phosphate, partially offsetting the effect of current high prices.

Alternative sources of phosphate could also be explored to replace ammoniated phosphate. However, alternatives such as NPKs and TSP are generally less accepted by farmers accustomed to DAP and MAP. Organic fertilizers represent another potential phosphorus source, but this market remains relatively small compared to mineral fertilizers and faces challenges related to quality and availability.

Given these considerations, addressing the DAP/MAP supply gap remains an urgent priority.

Conclusions

Phosphate fertilizers represent a critical component of agricultural productivity and food security, and current challenges of availability and affordability have placed immense pressure on farmers worldwide, particularly in price-sensitive regions.

Efforts to mitigate these challenges—such as exploring alternative fertilizers and approaches to bolster soil health, as well as improving application efficiency—are essential. Unfortunately, these cannot yet fully substitute for addressing the underlying supply constraints. More information is needed to better understand and effectively address this serious global trade and food production issue. One approach, proposed by the intergovernmental Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS) platform, seeks to expand transparency in terms of market fundamentals and pricing indicators, in order to better understand country impacts and navigate market uncertainty in an era of crisis.

Delphine Leconte-Demarsy is a Fertilizer Consultant with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization Investment Centre; Brendan Rice is a Research Specialist with IFPRI's Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit. Opinions are the authors'.