How do food and fertilizer price spikes and volatility impact Central America and the Caribbean?

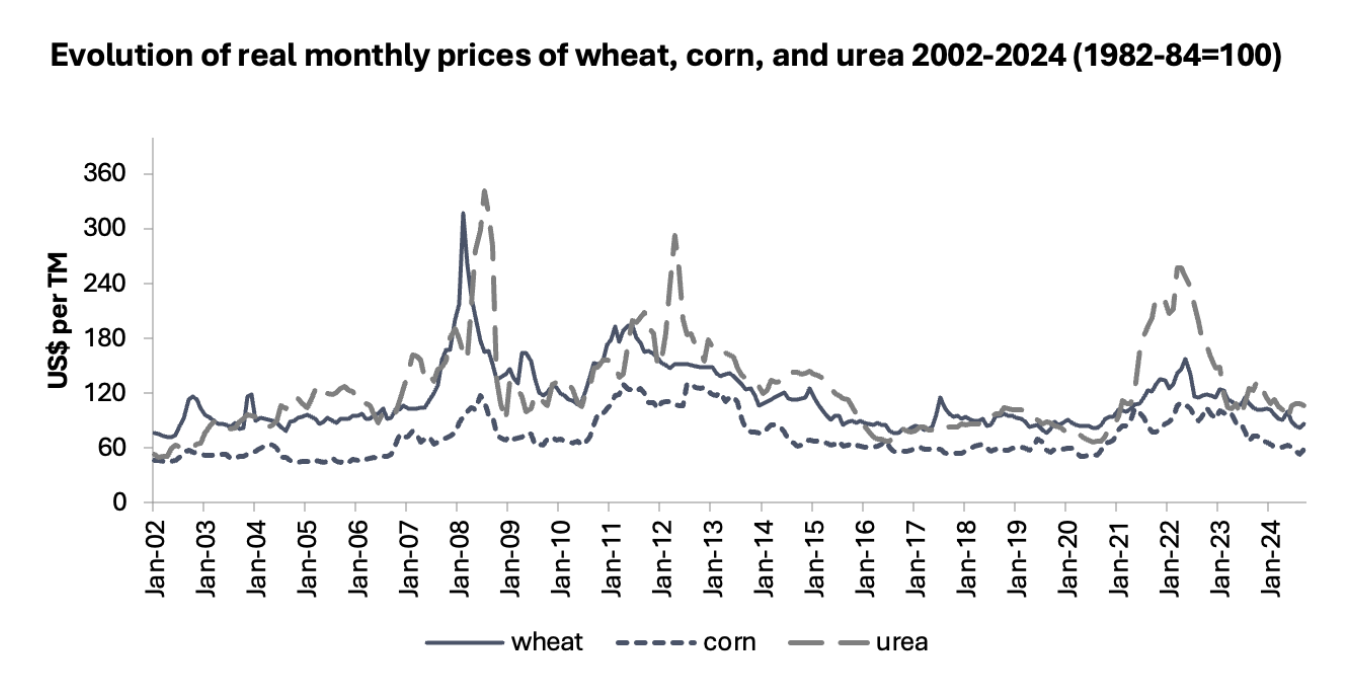

Recurring spikes and high volatility in international food and fertilizer prices (Figure 1) have triggered economic impacts around the world over the past two decades. These major shocks include the global food price crises of 2007-2008 and 2010-2011, the market disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine war. In the months after Russia’s February 2022 invasion, real global food prices reached the highest levels on record in more than six decades, while key global fertilizer prices more than doubled over those of the previous year.

Figure 1

Source: Authors. Prices are obtained from FAOSTAT. Wheat prices correspond to Canada Western Red Spring, corn prices to yellow corn No. 2 FOB from the U.S. Gulf, and urea prices to prill urea from the U.S. Gulf. MT=metric ton.

Rising and volatile food and fertilizer prices pose significant threats to food security and overall well-being among vulnerable populations, especially in developing countries. Food price inflation directly affects poor households’ ability to meet their food and nutrition needs, given that they spend a significant percentage of their income on food. More than 75 million people were pushed into extreme poverty in 2022, estimates show, while around 29% of the global population was moderately or severely food insecure in 2023. Similarly, recurrent price fluctuations affect small-scale farmers, who rely on food sales for a significant part of their income and possess limited capacity to time their sales. Price volatility may also distort input allocation, inhibit agricultural investment, and reduce agricultural productivity growth, especially in the absence of efficient risk-sharing mechanisms.

But to what extent are international food price spikes and volatility transmitted at the national level? This question has important policy implications. If transmission is high, efforts should primarily focus on stabilizing and reducing international prices, for instance through concerted multilateral actions at the global and regional levels. If transmission is low, and local price spikes and volatility likely depend mostly on domestic factors, then local price stabilization policies and investments would be the most effective instruments to protect vulnerable populations. In addition, separately assessing price and volatility transmission is relevant, since both do not necessarily go hand in hand.

A recent study by IFPRI and the World Bank examines the degree of price and volatility transmission from international to domestic food and fertilizer markets in seven countries in Central America and the Caribbean (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and the Dominican Republic). The study uses monthly international and domestic price data for 26 key food staples, cash crops, and fertilizers across the countries and relies on a multivariate generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (GARCH) approach—a robust statistical technique used to model volatility—to evaluate domestic responses to a shock in the international market. The analysis focuses on the level of transmission in the short run (one-month responses), permitting us to isolate the direct domestic response to an international shock. Focusing on the short-run level of transmission is warranted since vulnerable households, which typically face liquidity constraints, are thus less able to cope with short-term shocks.

Main findings

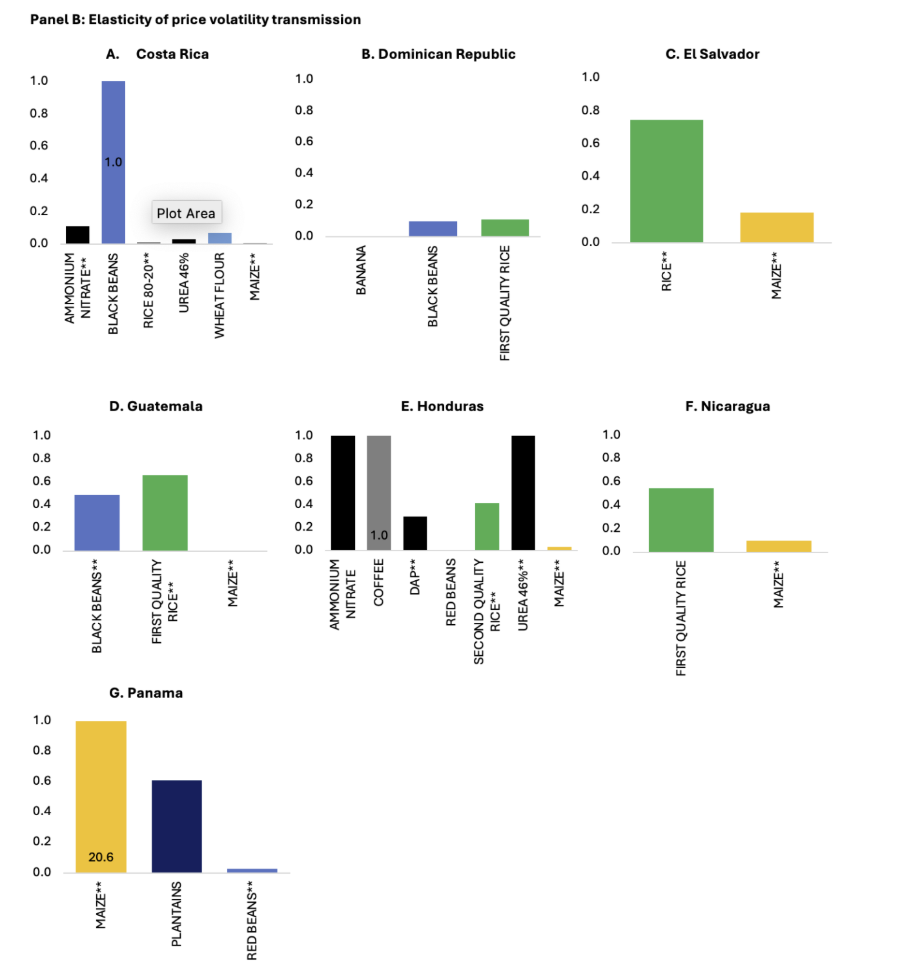

The study finds an overall low to moderate degree of price transmission, but a stronger degree of price volatility transmission, though the results vary depending on the country and the commodity (Figure 2).

Prices: The analysis finds a low degree of international-to-domestic price transmission for maize, beans, wheat, and bananas, but a moderate degree in rice, coffee, and fertilizers. Honduras shows some of the highest levels of price transmission across several products, while Guatemala and Nicaragua exhibit moderate price transmission for rice, and Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Panama have little to no evidence of price transmission.

Price volatility: The degrees of volatility transmission for maize, red beans, and wheat are low but generally higher than those of price transmission, while price volatility transmission for black beans is moderate and significantly higher than that of prices (especially for Costa Rica and Guatemala). Honduras also shows some of the highest degrees of price volatility transmission, particularly for coffee and fertilizers, along with rice.

Figure 2

Source: Authors. Panel A of the figure shows estimates for the elasticity of price transmission from international to domestic markets for each available country and commodity, while Panel B shows estimates for the elasticity of price volatility transmission (the figures in this panel are truncated to preserve scale where outlier values are indicated in bold). An elasticity greater (less) than one implies that, in the face of an exogenous shock that increases the price or price volatility of a given international price by one percent, the domestic price or price volatility for that commodity increases by more (less) than one percent. ** denotes a statistically significant estimate at the 5% level.

The study also explores the degree of co-movement between international and domestic prices over time, finding an increase linked to the 2007-2008 food price crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, although the results vary by country and commodities. For Costa Rica and El Salvador, for example, the degree of co-movement increased for some commodities such as maize and wheat after the 2007-2008 food price crisis, while for Honduras the degree of co-movement between international and domestic fertilizer prices increased after the 2007-2008 food price crisis, COVID-19 pandemic, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Finally, we attempt to infer the local welfare implications of global price and volatility increases by relying on simple back-of-the-envelope simulations. In particular, simulated international food and fertilizer price increases—mimicking the peak inflation observed in 2022—reveal small yet non-negligible effects on local consumer and producer welfare. For instance, in Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, an increase in the international price of rice is estimated to improve welfare for the average household, with the positive effect on households that are net sellers of rice compensating for the negative effect on net consumer households. In contrast, an increase in the international price of maize is estimated to hurt households on average in Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. An increase in the international price of urea, in turn, is estimated to have a larger negative effect on average rural incomes in Honduras than in Costa Rica. These simulated effects, however, cannot explain on their own the magnitude or full range of effects of the region’s food security crisis in recent years.

Key insights and future work

Overall, our findings indicate small to moderate levels of international-to-domestic price transmission in the region. Such imperfect pass-through suggests the presence of other factors, particularly domestic ones, influencing local prices. We partially attribute these findings to the degree of domestic dependence on imports and exports of the different commodities, though other possible factors at play include specific domestic policies and regulations (such as price controls for key food staples or trade restrictions, to mention a few), as well as the role of market concentration (degree of competition) across global and local input and food supply chains and their distribution channels.

The findings have implications for food price crisis policy responses. When global food and fertilizer prices spike, some countries (including several in the region) seek to shield domestic economies via export restrictions, input subsidies, and other measures. However, this approach may also result in relative price distortions of inputs and products and lead to inefficient or unsustainable production or consumption practices in the long run. Studying in more detail the different factors that may affect the relationship between international and domestic prices remains an important avenue for future research, as more granular data become available.

The recurring food crises of recent years underscore how important it is to closely monitor global food prices and fluctuations—and to study their effects on domestic markets. A key focus should be specific commodities such as rice, coffee, and fertilizers that appear to be more connected to global markets and exhibit a relatively higher degree of price volatility transmission. Early warning systems such as IFPRI’s Excessive Food Price Variability tool, which tracks unusual price fluctuations in major agricultural, food, and energy commodities, can be helpful for informing appropriate and timely responses.

Manuel Hernandez is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit; Francisco Ceballos is an MTI Research Fellow; Maria Lucia Berrospi is an MTI Research Analyst. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed. Opinions are the authors’.