How Trump tariffs might impact countries of Latin America and the Caribbean

Donald Trump’s return to the White House likely also signals the return of the unilateral trade policies that characterized his first term and precipitated trade wars between the United States and many of its trading partners, most notably China. As a candidate, the president-elect threatened a number of adverse trade actions including raising tariffs on all imports by 10%-20%. He has warned a number of specific countries as well—suggesting he would consider 60% tariffs on China and 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico.

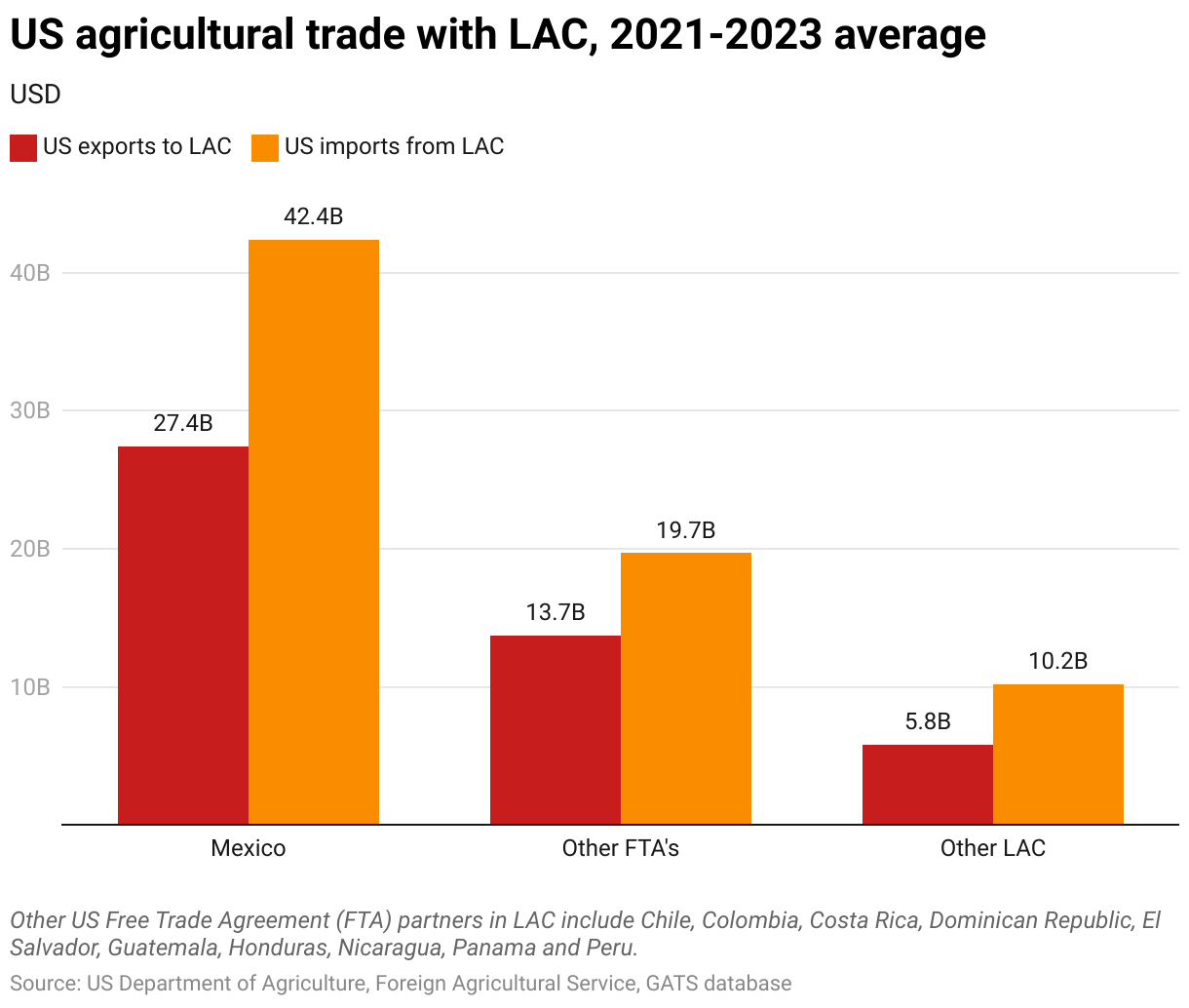

In this post, we examine the potential disruptions—and some possible opportunities—of a bellicose U.S. trade policy for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), whose countries number among the closest U.S. trading partners for agricultural products. High tariffs would represent a major policy reversal, as many U.S. agricultural imports currently have low (or zero) tariffs, particularly those coming from the countries that have FTAs with the United States (Figure 1). Among other impacts, increasing tariffs on LAC countries would significantly raise prices for those commodities for U.S. consumers.

Figure 1

The United States imported more than $72 billion of agricultural products from LAC from 2021-2023 (Figure 2). Agricultural imports from Mexico predominate, accounting for $42 billion. Imports from other LAC countries with which the U.S. has free trade agreements (FTAs) totaled $15 billion over the same period (those countries include Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominical Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and Peru).

A new round of U.S. tariffs would certainly hurt LAC exporters if applied universally across all countries. If tariffs are targeted towards one country (for example, Mexico or China) that could create opportunities for some LAC exporters to make gains in U.S. markets. LAC countries such as Brazil or Argentina could also make significant export gains in third markets (for example, China) if their governments target the U.S. with countervailing retaliatory tariffs.

Figure 2

Vulnerability of LAC agricultural exports to U.S. tariffs

Dependence on the U.S. market varies widely among LAC markets (Figure 3). Mexico is by far the most vulnerable among LAC exporters—almost 92% of Mexico’s agricultural exports went to the United States in 2023. Dependency on the U.S. market is quite high for other countries with FTAs as well: Dominican Republic (58%), Nicaragua (43%), Colombia (40%), Peru (35%) and Chile (19%).

Figure 3

While the U.S. market is less important for large exporting countries such as Argentina (3% of total agricultural exports) and Brazil (4% of total agricultural exports), the United States remains a significant buyer, particularly for certain commodities. For example, U.S. imports of Brazil coffee exceeded $1.7 billion in 2023, while imports of orange juice from Brazil were almost $700 million.

Potential impact of trade diversion on LAC exporters

Now let us consider the impacts on LAC exporters if tariff increases are targeted towards individual countries. For example, Trump has threatened 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada, the top two U.S. agricultural import suppliers. Table 1 shows U.S. imports for the top 10 product groups in 2023 from those countries. For many of these items, sharply increasing tariff levels could open opportunities for other LAC exporters.

Table 1

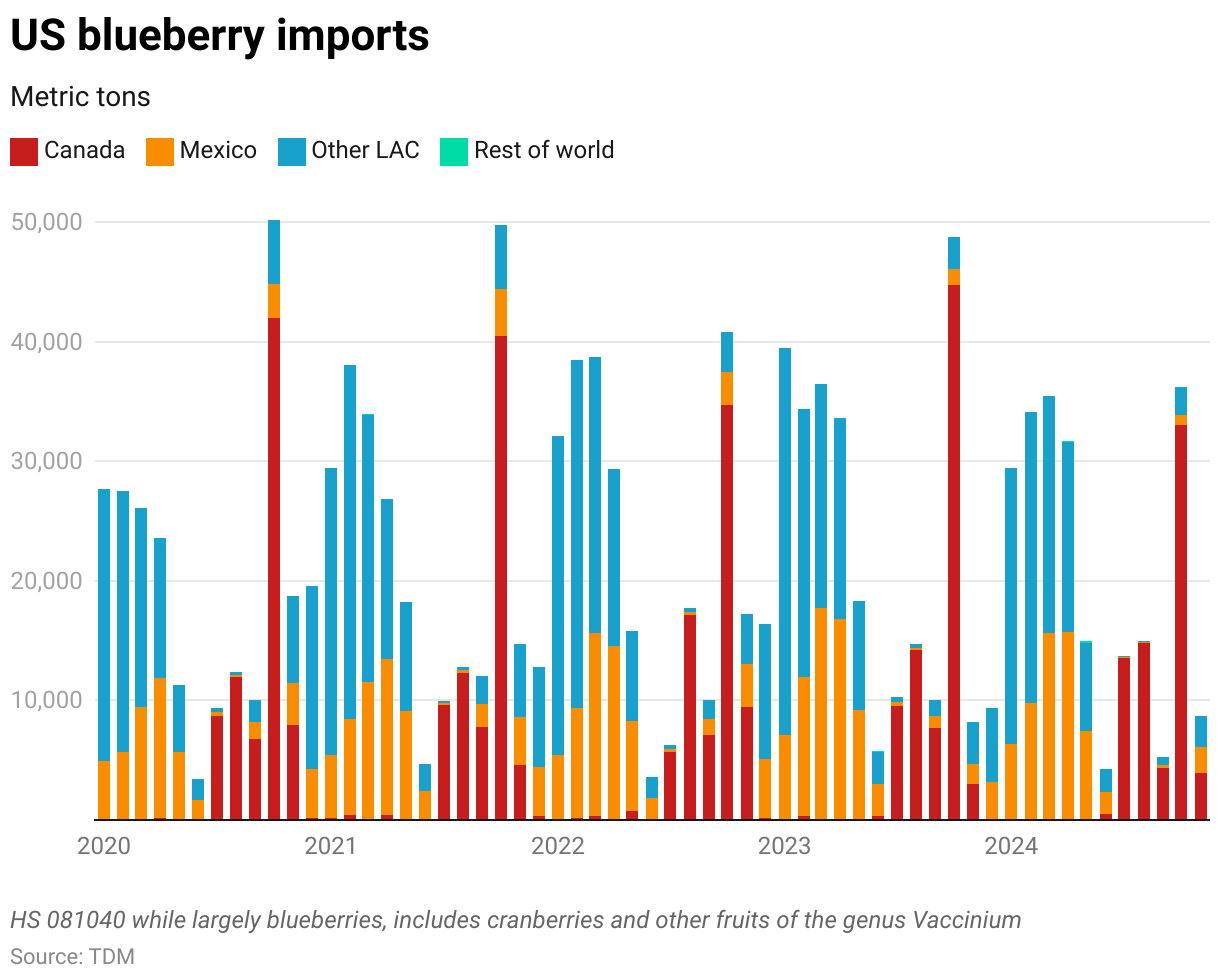

Consider blueberries. U.S. blueberry imports in 2023 were $1.8 billion, about $700 million from Mexico and Canada. Imports from Peru and Chile totaled over $870 million and about $200 million, respectively (Figure 4). If high tariffs reduce Mexican imports, the loss could be partially offset by imports from Peru and Chile. But that in turn would have broader impacts, as those countries would end up diverting blueberries to the U.S. from other markets (for example, the European Union)—as it is difficult to increase relative supplies in the short run. (It normally takes three or more years to bring a blueberry plant to full maturity.)

Figure 4

Impacts of counter-retaliatory actions against U.S. exports

Then there is the possibility of trade warfare. Unilateral trade actions could provoke counter-retaliatory measures against U.S. exports—something that could open up increased export opportunities in third markets for LAC exporters.

In 2018, some of America’s largest and most significant trading partners imposed retaliatory tariffs on U.S. agricultural exports—including Canada, China, the EU, Mexico, India, and Türkiye. Those measures affected U.S. agricultural exports worth an estimated nearly $30 billion in 2017, including livestock, dairy products, horticultural products, specialty crops, processed foods, beverages, tobacco, and cotton.

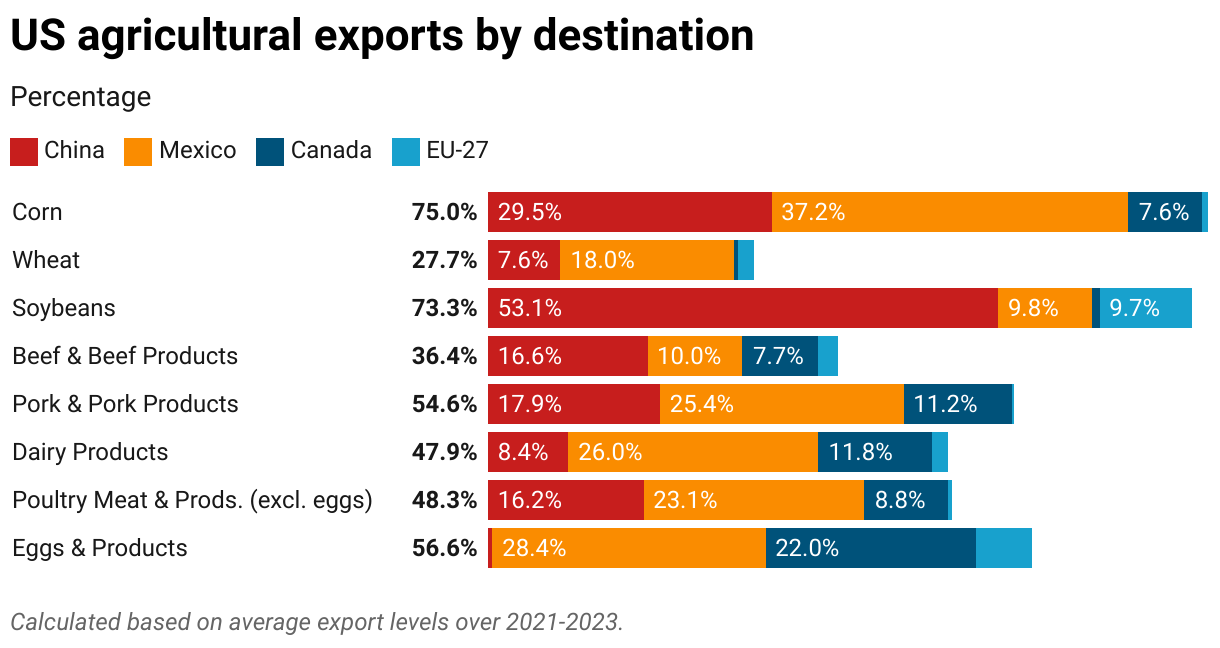

Canada, China, Mexico, and the EU are important destinations for many U.S. agricultural exports (Figure 5). For example, over 75% of U.S. corn exports, 73% of U.S. soybean exports and 55% of U.S. pork exports went to these four markets during 2021-2023. Counter-retaliatory tariffs could open export opportunities for countries such as Brazil (corn, soybeans, pork, beef and poultry), Argentina (corn, wheat, soybeans, beef) and Uruguay (dairy).

Figure 5

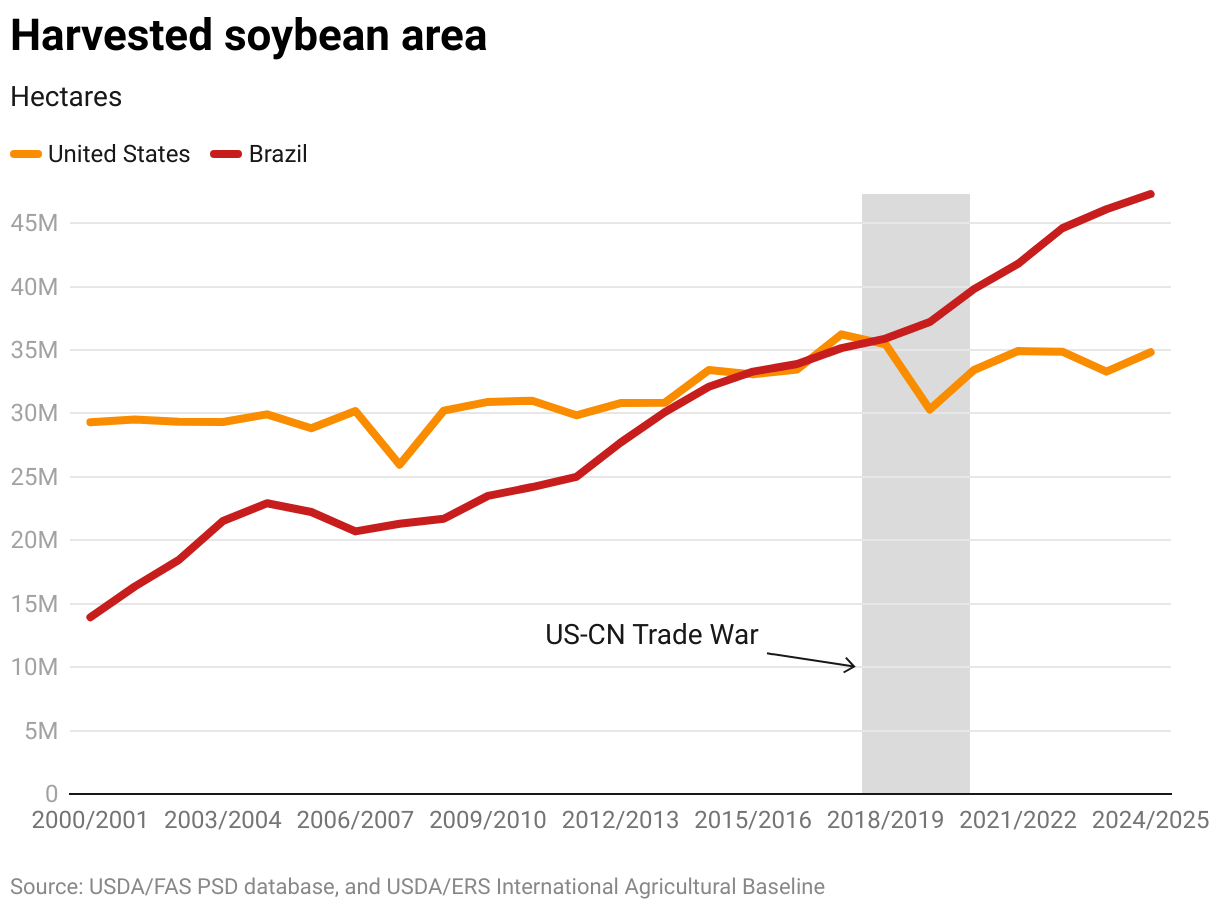

The 2018-19 trade war with China offers more evidence of such effects. The U.S. share of China soybean imports plummeted from 34% in 2017 to 19% in 2019, while U.S. feed grains exports fell from 33% of China’s imports in 2017 to about 8% in 2019 (Figure 6). Brazil was the main beneficiary of the soybean dispute. Brazil soybean exports to China increased 29% in 2018 and Brazil’s market share increased from 53% in 2017 to 75% in 2018.

Figure 6

If similar trade brinkmanship happens in the next Trump administration, it might be difficult in the short run for LAC exporters to fully offset the decline in U.S. exports affected by counter-retaliatory tariffs; but if the experience of the 2018-19 U.S.-China trade war is a guide, LAC exporters would likely gain as they did in 2018 from higher prices.

Between 2018 and 2020, Brazilian soybean area increased by almost 4 million hectares—more than 10%—in part driven by higher prices due to the U.S.-China trade war (Figure 7). By contrast, counter-retaliatory tariffs and the loss of the China market caused U.S. soybean prices to fall and soybean area dropped 5 million hectares (more than 14%) from 2018 to 2019 (recovering marginally in 2020)

Figure 7

Conclusions

We don’t yet know what type of trade actions the new Trump administration will implement after assuming power on Monday. Some reports suggest that tariffs will be applied strategically in a more limited scope than originally articulated by candidate Trump (something the president-elect has denied). Other reports suggest that tariff increases could be phased in gradually.

Regardless of their scope and timing, trade wars are inherently disruptive and can create large distortions in world trade flows and prices—affecting producers and consumers, with many hard-to-predict impacts on markets from the global to the local level. The prospects of renewed trade wars in a new Trump Administration have created significant uncertainty as farmers in the United States and elsewhere brace for potential impacts. The impact on LAC countries would likely be mixed. For countries like Mexico that have FTAs with the United States, imposition of across-the-board tariffs could have large impacts on their agricultural exports and export earnings. For countries like Brazil and Argentina, where the U.S. is a small percentage of their overall export profile, the impacts of tariff increases will be smaller, although individual items (like coffee) could be hurt.

As one of the world’s largest agricultural importers, the United States is hardly immune to blowback from its own tariffs. Higher food prices could pinch consumers just recovering from recent bouts with inflation. If countries respond as they did during previous trade wars by imposing counter-retaliatory tariffs, U.S. producers could be the big losers as they were in 2018 and 2019. In the short run, they would likely face lower farm prices as exports plummet. In the long run, U.S. producers could also lose as their reputation as reliable suppliers suffers and trade is diverted to other suppliers ready to step in—including LAC.

Joseph Glauber is a Research Fellow Emeritus with IFPRI's Director General’s Office; Juan Pablo Gianatiempo is a Research Analyst with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit. Opinions are the authors'.